Researchers have found that melanoma cells fight anti-cancer drugs by changing their internal skeleton (cytoskeleton) – opening up a new therapeutic route for combatting skin and other cancers that develop resistance to treatment.

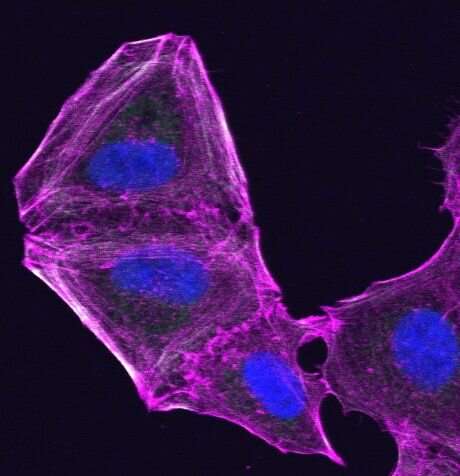

The team, led by Queen Mary University of London, found that melanoma cells stop responding to both immunotherapies and drugs targeted at the tumour’s faulty genes (B-RAF or N-Ras mutations in the MAPK pathway) by increasing the activity of two cytoskeletal proteins—ROCK and Myosin II. The team found that these molecules were key for cancer cell survival and resistance to these treatments.

The molecules had previously been linked to the process of metastatic spread but not to the poor impact of current anti-melanoma therapies. This work points to a strong connection between metastasis and therapy resistance—confirming that the cytoskeleton is important in determining how aggressive a cancer is.

The findings are published in the journal Cancer Cell today.

Malignant melanoma has very poor survival rates despite being at the forefront of personalised immunotherapy. This is largely due to the development of resistance. Around 16.000 people in the UK are diagnosed with malignant melanoma each year, with more than 2,300 deaths.

Tests in mice suggest that the therapy resistant (or non-responding) tumours are effectively addicted to ROCK-Myosin II to grow. The team discovered that blocking the ROCK-Myosin II pathway not only reduces cancer cell growth, but also attacks faulty immune cells (macrophages and regulatory T cells) that are failing to kill the tumour. This action boosts anti-tumour immunity.

Lead author Professor Victoria Sanz-Moreno, Professor of Cancer Cell Biology at Queen Mary, said: “We were very surprised to find that the cancerous cells used the same mechanism, changing their cytoskeleton, to escape two very different types of drugs. In a nutshell if you are a cancer cell, what does not kill you makes you stronger. However, their dependence on ROCK-Myosin II is a vulnerability that combination drug therapy tests on mice suggest we can exploit in the clinic by combining existing anti-melanoma therapies with ROCK-Myosin II inhibitors.”

She said the research may have implications for cancers with similar faulty genes.

First author Jose L. Orgaz, Research Fellow at Queen Mary’s Barts Cancer Institute, said: “An important observation was finding increased Myosin II activity levels in resistant human melanomas, which suggests the potential as a biomarker of therapy failure. Resistant melanomas also had increased numbers of faulty immune cells (macrophages and regulatory T cells), which could also contribute to the lack of response.”

Source: Read Full Article