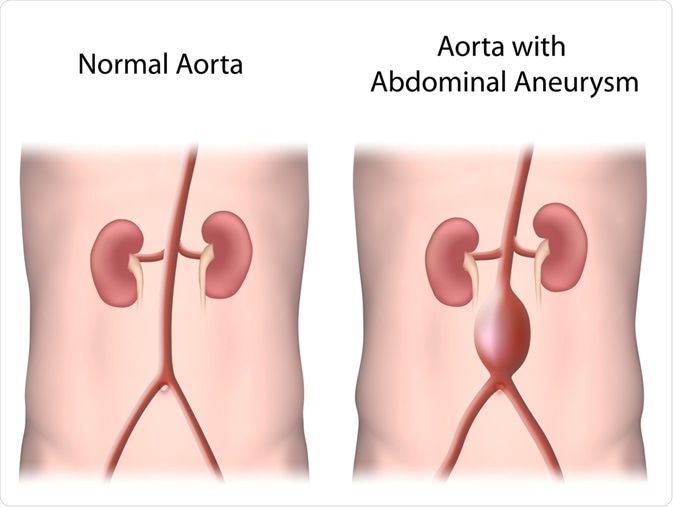

An abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is defined as a bulge or dilation of the abdominal aorta, the largest blood vessel in the abdomen. It occurs when the wall of the abdominal aorta becomes weakened and the continued pressure of the blood flowing through the vessel causes it to bulge outwards to over twice its size. Without treatment, the aorta will continue to bulge and could rupture, causing life-threatening internal bleeding.

Skip to:

- Causes of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms

- Classification and Symptoms

- Epidemiology (USA and UK)

- Prognosis

- Managing and Treating an Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm

Causes of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms

Aneurysms can occur anywhere in the body; however, the most common sites for aneurysms are in the abdominal aorta and the brain. The exact cause of the weakening of the vessel walls is unknown. However, several risk factors that may contribute to the weakening of blood vessel walls have been identified.

Risk factors include:

- Smoking (by far the greatest risk factor for AAA),

- Hypertension (high blood pressure),

- Atherosclerosis (hardening of the arteries),

- Any disease that causes chronic inflammation of the arteries.

Alila Medical Media | Shutterstock

Alila Medical Media | Shutterstock

In most cases, an abdominal aortic aneurysm causes no noticeable symptoms and may, therefore, go undiagnosed for a long period of time. This is particularly dangerous as large aneurysms are increasingly likely to rupture. A ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm can, in turn, cause massive internal bleeding that may almost certainly lead to death if not contained immediately.

The most common symptom of a ruptured aortic aneurysm is sudden and severe abdominal or back pain that does nt go away.

Classification and Symptoms of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms

Abdominal aorta aneurysms can be classified based on their shape (most common), rupture status, size, and dissection status. The classification status is used to determine whether an aneurysm is present, how serious it is, and make decisions about treatment.

Aneurysm shape

Classification based on shape includes saccular aneurysms, which are asymmetrical and appear on one side of the aorta, and fusiform aneurysms, which appear as symmetrical bulges around the circumference of the aorta. Saccular aneurysms are usually caused by injury or a severe aortic ulcer, but fusiform aneurysms are the most common shape of an aneurysm.

Rupture status

Rupture status presents another possible classification set and is determined based on the patient’s symptoms. Unruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms are the more common form of aortic aneurysm. Typical symptoms of an unruptured AAA include:

- Pain in the loins, stomach, or lower back – caused by the pressure of the aneurysm on the vertebrae and spinal cord,

- A pulsating mass (similar to a heartbeat) in the abdomen,

- Fibrosis and adhesions around the abdomen, which may compress abdominal structures such as the intestines.

Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms are possible among patients with severe fall in blood pressure. The bursting of an abdominal aortic aneurysm is associated with:

- Sharp, severe pain in the stomach, lower back or loin,

- A severe loss of blood pressure, which may cause intense sweating, shock, collapse and black out.

- Death – fatalities occur in 85-95% of all cases of ruptured AAA, unless the patient is immediately transferred to the hospital and bleeding is stopped.

Size and dissection status

Two other ways of classifying abdominal aortic aneurysms is according to their size and dissection status. Sizewise, an aneurysm is usually defined as an outer aortic diameter over 3 centimeters (normal diameter of aorta is around 2 centimeters).

Dissection status refers to when the inner layer of the wall of the aorta tears, leading to the layers of the wall separating. This is a form of rupture known as a dissecting aneurysm and weakens the wall of the aorta.

Epidemiology (USA and UK)

Abdominal aortic aneurysms are believed to be more common than the reported numbers, as many cases go undetected and unreported. On a global level, there is a decrease in both incidence and prevalence of the disease, but with potential increases in certain parts of Latin America and Asian-Pacific countries.

The frequency of abdominal aortic aneurysms varies strongly between males and females, however, the majority of cases occur in males around 70 years of age. Over 60 years of age, the rate of abdominal aortic aneurysm among males is 2-6%. Some ethnicities are naturally less susceptible to abdominal aorta aneurysms, such as individuals of African, Asian, and Hispanic origin.

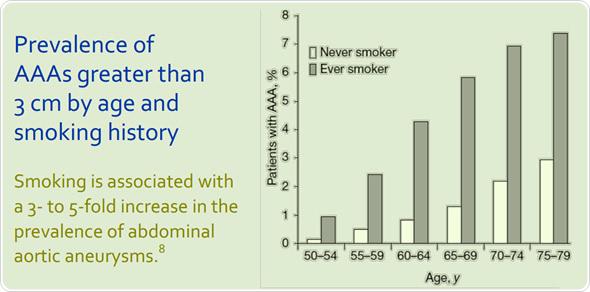

Smokers have a higher rate of abdominal aorta aneurysms than non-smokers, with around 8 times higher risk of developing AAA compared to non-smokers. Smoking is more detrimental as a risk factor in women than in men, and the risk reduces gradually after cessation of smoking.

United States

In the United States, the incidence of abdominal aorta aneurysms is 2-4% in the adult population. It is seen that brothers of patients with abdominal aorta aneurysms are at a four to six times greater risk of the condition with a risk of 20-30%.

AAAs may rupture or lead to dissection in a lower number of individuals. Aortic dissections are responsible for at least 15,000 deaths every year in the USA and ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms occur in 1-3% of men aged 65 or older, with a mortality rate of 70-95%.

United Kingdom

In the UK, abdominal aortic aneurysms commonly affect men over 65 with around in 1 in 25 men being affected. However, the rates of rupture are rare, with only around 1 in 10,000 people having a ruptured AAA in any given year in England. Presence of symptoms of the aneurysm is noted in around 25 per 100,000 at age 50. This number is sharply increased to 78 per 100,000 in those over the age of 70.

The incidence of newly reported cases of AAA was found to be on the rise between 1970 and 2000 in the UK. This could be due to the advent of smokers and the rise of dyslipidemia (high blood cholesterol) and obesity. These risk factors have led to an increase in cases of atherosclerosis, which are known to increase the likelihood of an aneurysm. However, this trend appears to be decreasing in recent years with the advent of effective cholesterol-lowering medications and a decline in smoking rates.

As a result, the UK NHS launched a screening service to assess males over 65 years for abdominal aortic aneurysms. Diagnosis can be made by non-invasive tests like imaging studies, including ultrasonography, CT scan, and MRI. MR angiography reveals the clearly defined size and structure of the aneurysm and aids in planning surgery.

Prognosis

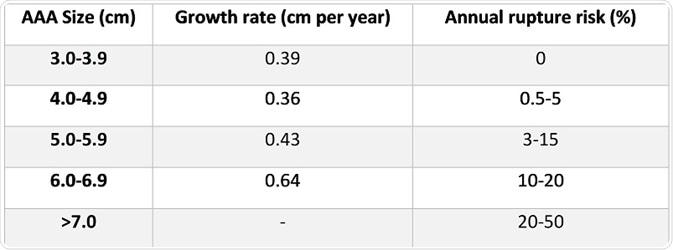

The prognosis of an abdominal aortic aneurysm depends on the size and location of the aneurysm, in addition to various other patient-related factors. The risk of rupture, which in many cases leads to fatality, is mainly determined by aneurysm diameter.

This is diagnosed using the finite element method (FEM), a common engineering technique, to determine the wall stress distributions. These stress distributions correlate with the overall geometry of the abdominal aorta aneurysm rather than the maximum diameter alone.

The principles show that wall stress is not the only factor that governs rupture because the aneurysm will rupture when the wall stress exceeds the wall strength. Thus, both patient-specific wall stress and patient-specific wall strength needs to be calculated to assess the precise risk of rupture.

Normally the aneurysm gradually expands each year by approximately 10% of the initial arterial diameter. For aneurysms that are over 5cm in diameter, surgery is required. Without surgery, the annual survival rate is a mere 20%.

Normally the aneurysm gradually expands each year by approximately 10% of the initial arterial diameter. For aneurysms that are over 5cm in diameter, surgery is required. Without surgery, the annual survival rate is a mere 20%.

The risk of rupture of the abdominal aortic aneurysm increases with size, wherein aneurysms larger than 6 cm have a 25% annual risk of rupture.

Following the rupture of an abdominal aortic aneurysm, the risk of death is approximately 80%. Most patients die before reaching the hospital. In most patients, the outcome is poor and surgical repair is only successful in 50% of cases with a ruptured aneurysm.

Elective surgeries are sometimes carried out to prevent rupture. The rate of success of elective surgery for aneurysm correction depends on the patient’s fitness for surgery and the type and location of the aneurysm. Those patients who have other medical disorders, like heart disease and kidney disorders, have a high risk of failed surgery and complications due to surgery.

Some of the more recently proposed abdominal aorta aneurysm rupture-risk assessment methods include assessment of:

- Abdominal aorta aneurysm wall stress

- Abdominal aorta aneurysm expansion rate

- Degree of asymmetry

- Rupture potential index (RPI)

- Finite element analysis rupture index (FEARI)

- Biomechanical factors coupled with computer analysis

- Geometrical parameters of the abdominal aorta aneurysm

Managing and treating an Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm

Abdominal aorta aneurysm may be treated in two ways – preventive treatment and emergency treatment. Under preventive treatment, the aim of surgery and medical therapy is to prevent the rupture of the aneurysm. Under emergency treatment, the focus is on repairing the aneurysm after it has ruptured.

Preventative surgery

Preventive surgery carries its own risks and is usually only recommended if the risk of a rupture is high enough to justify the risk of surgery. To undertake preventive surgery first a risk assessment is made to determine the likelihood of the aneurysm rupturing.

This is based on the age of the patient, general health (ability to withstand surgery), size of the aneurysm, rate of growth of the aneurysm, and history of ruptured aneurysms in a close relative. Risk assessments also look at blood levels of a chemical called matrix metallopeptidase 9 (MMP-9), which is present in excessive levels when the aortic wall weakens extensively.

If the aneurysm is 5–5.5 centimeters (2–2.2 inches) and there is a concern that it may rupture, preventive surgery is advised. Surgery is usually recommended if the aneurysm is larger than 5.5 centimeters regardless of whether there are other risk factors present.

The most common surgical treatment for an abdominal aortic aneurysm is grafting. Grafting involves the affected section of the aorta being removed and replaced with a piece of synthetic tubing, known as a graft. This is also called a stent graft and holds the aorta open like a scaffold.

Grafting can be carried out using two different approaches:

- Open surgery – where a large incision is made over the abdomen and the surgery is performed,

- Endovascular surgery – where a thin tube called a catheter is inserted into one of the arteries in the legs and the graft is guided within the catheter into the aorta.

The graft is placed at the site of the aneurysm to reinforce the aorta wall. In most cases, endovascular surgery is recommended due to improved outcomes than open surgery for preventing death from a ruptured aneurysm and other complications.

The success of endovascular surgery depends on the aortal morphology and also the associated arteries, but it can be pursued safely even in those older than 80 years of age. Quality of life scores are also better with endovascular surgery when compared to open surgery.

Emergency treatment for an abdominal aortic aneurysm

Emergency treatment for a ruptured aortic aneurysm is based on the same concepts as preventive surgery. Similar grafts are used to repair the ruptured aneurysm. However, time is vital in ruptured aneurysms and there is additional medications are often used to prevent blood loss and organ damage. For example, nimodipine is given to prevent ruptured blood vessels going into spasm and causing further blood loss. A blood transfusion may also be provided.

Managing an abdominal aortic aneurysm through medication and lifestyle changes

For those with an abdominal aortic aneurysm less than 5 centimeters, observation with repeated ultrasound examinations is usually recommended. Ultrasound scans are prescribed every three to six months to check for any growth of the aneurysm.

Medications may also be used to lower the risk of aneurysm. For example, those with high blood cholesterol are given cholesterol-lowering medications like statins, and those with high blood pressure may be given angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors.

In all cases, lifestyle changes (including smoking cessation) are strongly recommended. Smoking carries the greatest risk of aneurysm, as smokers typically show faster-growing aneurysms than non-smokers, and larger aneurysms show an elevated rupture risk. Patients are advised to exercise regularly and maintain a balanced diet in order to maintain a healthy body weight.

Sources

Abdominal aortic aneurysm. NHS.

Aortic Aneurysm Fact Sheet. CDC.

AAA Screening. NHS Wales.

Heart, Vascular and Thoracic Care. UW Health.

Abdominal aortic aneurysm. Mayo Clinic.

BRIAN KEISLER, MD, and CHUCK CARTER, MD. 2015. Am Fam Physician. 15;91(8):538-543.

Abdominal aortic aneurysm: update on pathogenesis and medical treatments. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2019. Apr;16(4):225-242. DOI:10.1038/s41569-018-0114-9

Abdominal aortic aneurysms. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018. Oct 18;4(1):34. doi: 10.1038/s41572-018-0030-7.

Further Reading

- All Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Content

Last Updated: Jan 13, 2021

Written by

Sara Ryding

Sara is a passionate life sciences writer who specializes in zoology and ornithology. She is currently completing a Ph.D. at Deakin University in Australia which focuses on how the beaks of birds change with global warming.

Source: Read Full Article