A study of antibiotic prescription rates for Aboriginal children in remote communities in the Northern Territory (NT) has identified high rates of infections and antibiotic use in these communities.

The study, Antibiotic use for Australian Aboriginal children in three remote Northern Territory communities, was recently published in the journal PLOS ONE.

Led by Menzies School of Health Research (Menzies), the study gathered antibiotic prescription data from 124 electronic health records for children aged under two years old in three remote communities in the NT, finding prescription rates to be six times higher than those reported in other studies for non-Aboriginal children in urban areas.

Lead author, Menzies’ Timothy Howarth said the study addresses the data gap for how antibiotics are prescribed by remote Primary Health Centres (rPHC) identifying that for the majority of infections reported, the appropriate antibiotic had been prescribed.

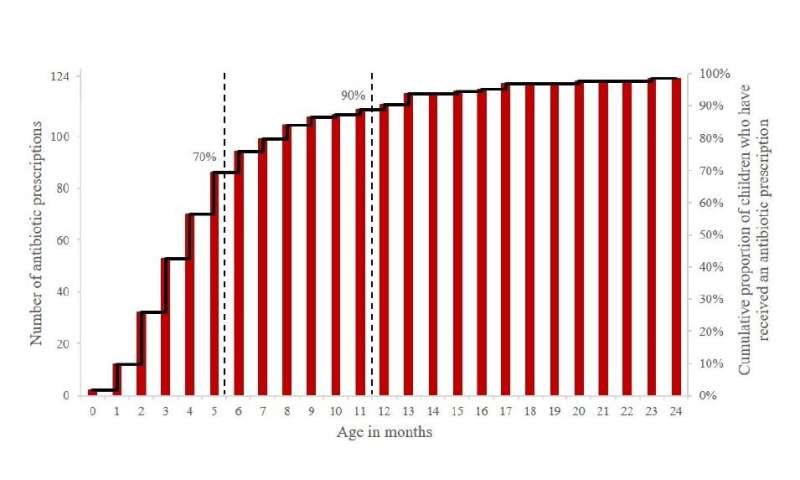

“We found that by 12 months of age, 90 percent of Aboriginal children in this study had received at least one antibiotic prescription. This is significantly higher than that reported in other studies for non-Aboriginal children. Treatment for otitis media alone, accounted for 30 percent of prescriptions,” Tim said.

“Even though the rate of prescriptions is higher we also found that the tracking of prescriptions here is significantly better than the wider Australian community—70 percent of prescriptions had an indication recorded which could be tracked for appropriateness and two-thirds were considered appropriate.

“When comparing this to primary care data in wider Australia, only 25 percent of prescriptions had an indication recorded, of which one-third were considered appropriate.”

Co-author and Menzies senior research fellow, Dr. Thérèse Kearns said that it is critical to address the underlying determinants of health to reduce the burden of disease which underpins antibiotic prescription rates.

“A major strength of the study was the level of clinical information available within the electronic health record and that legislative requirements placed on nurses and Aboriginal Health Practitioners to supply and administer antibiotics was effective in limiting inappropriate antibiotic use in this setting,” Dr. Kearns said.

Source: Read Full Article