Millions of Americans braced for the week ahead with no school for their children for many days to come, no clue how to effectively do their jobs without child care, and a growing sense of dread about how to stay safe and sane amid the relentless spread of the coronavirus.

Are play dates for the kids OK? How do you stock up on supplies when supermarket shelves are bare? How do you pay the bills when your work hours have been cut? Is it safe to go to the gym? And how do you plan for the future with no idea what it holds?

“Today looks so different from yesterday, and you just don’t know what tomorrow is going to look like,” said Christie Bauer, a family photographer and mother of three school-age children in West Linn, Oregon.

Tens of millions of students nationwide have been sent home from school amid a wave of closings that include all of Ohio, Maryland, Oregon, Washington state, Florida and Illinois along with big-city districts like Los Angeles, San Francisco and Washington, D.C. Some schools announced they will close for three weeks, others for up to six.

The disruptions came as government and hospital leaders took new measures to contain an outbreak that has sickened more than 150,000 people worldwide and killed about 5,800, with thousands of new cases being confirmed every day.

As the U.S. death toll climbed to 51 on Saturday and infections totaled more than 2,100, President Donald Trump expanded a ban on travel to the U.S. from Europe, adding Britain and Ireland to the list, and hospitals worked to expand bed capacity and staffing to keep from becoming overwhelmed as the caseload mounts.

“We have not reached our peak,” said Dr. Anthony Fauci of the National Institutes of Health. “We will see more cases, and we will see more suffering and death.”

Many working parents are scrambling to find child care, even if they are being allowed to work from home. The child care needs are especially dire for the legions of nurses, hospital and health care workers across the country who need to be on the job to deal with the crisis.

Governors drew up emergency plans to find child care for front-line medical workers and first responders, equating it to a wartime effort.

“I would put this as a World War II-capacity daycare for our public health workers because we’re going to need every single body we can get,” said Oregon Gov. Kate Brown.

Parents desperate to get to work with schools closed have jumped on social media boards to seek child care or to exchange tips about available babysitters.

Seattle resident John Persak set up a Facebook group last week for parents with children at home because of school closings. The group exploded to nearly 3,000 members.

“We’re getting about five requests a minute at this point,” said Persak, a father and crane operator at the port of Seattle, who said his work hours have been curtailed for weeks by the coronavirus outbreak, which is affecting cargo deliveries from Asia.

In Maryland, where schools will be closing from Monday through March 27, parents are calling up their kids’ former nannies and babysitters.

“They are desperate,” said Ellen Olsen, who has been a nanny for more than 11 years and co-manages a Facebook group that connects parents, nannies and sitters in Maryland. “We’ve seen a lot of parents posting, ‘Hey, schools are closed, but I still have to work.'”

Olsen takes care of two babies, but starting next week, two girls ages 9 and 11 whom she once watched will also be under her supervision. Olsen said the girls’ parents are doctors and asked for her help after school was canceled.

New York Mayor Bill de Blasio defied mounting pressure to close the nation’s biggest school system, saying shutting the schools for the more than 1.1 million students could hamper the city’s ability to respond to the crisis by forcing parents who are first responders and healthcare workers to cast about for child care or stay home.

“Many, many parents want us to keep schools open,” he said. “Depend on it. Need it. Don’t have another option.”

The cascade of closings upended weekend routines for countless mothers and fathers. Little League and other sports were canceled. Parks were closed. Play dates were upended. The size of the crowd at a public library in suburban Portland rivaled that of the neighborhood Costco as parents scrambled to stockpile books for children.

While some people were opting to isolate themselves, not everyone was ready to put their lives on hold.

Despite the cancellation of St. Patrick’s Day parades around the country and pleas to curtail public gatherings, pub celebrations continued in many places. In Chicago, pub crawls and other revelry went ahead as planned, prompting an angry rebuke from Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker.

“If you are young and healthy, listen up: We need you to follow social distancing, too,” Pritzker said, urging partygoers to go home.

Spring Break partying in Florida also prompted official action, with authorities closing South Beach to prevent the virus’ spread. Miami Beach officials ordered hundreds of college spring breakers and others from around the world off the beach Saturday and eliminated parking on major streets in the city’s entertainment district to cut down on crowds at South Beach clubs and restaurants.

In New York City, where de Blasio called the scramble to fight the coronavirus a “wartime scenario,” a passer-by who noticed relatively light crowds at a Whole Foods supermarket on Manhattan’s Upper East Side remarked: “That’s because there’s no food left!”

That was far from true, though some items—frozen foods, canned tuna, herbal teas, bagged salad—were sold out or nearly so. Signs limited customers to two large packs of toilet paper apiece, and few were available. A similar scenario played out at supermarkets all around the country amid a run on household staples that reached a peak Friday.

San Antonio-based H-E-B, a grocery chain with more than 400 stores in Texas and Mexico, is reducing its late-night store hours to discourage hoarding and give it time to restock.

“There is no need for panic buying, this is not like a hurricane,” H-E-B spokeswoman Dya Campos said. “This should not be a ‘stock up’ event.”

Bauer, the photographer in Oregon, said the bans and fear of travel have hit her professional and personal life. First, a photography workshop she was set to attend in Greece was canceled. Now, she and her husband are trying to decide whether to cancel their spring break trip to Charleston, South Carolina, next week.

“We’re worried we’ll get stuck out there or get there and be sick,” Bauer said. “There’s just so much unknown that you don’t know what to do at the moment.”

Keeping occupied was becoming challenging, for both children and adults, with so many businesses closed and uncertainty about whether routines like going to the gym were still advisable.

Minnesota resident Nancy Patton said she was sticking to her yoga class, for now, because it helped her feel mentally and physically healthy.

On Saturday, Patton was leaving a yoga class at a gym in the Minneapolis suburb of Plymouth, where she said “social distancing” was in effect with more space between each person.

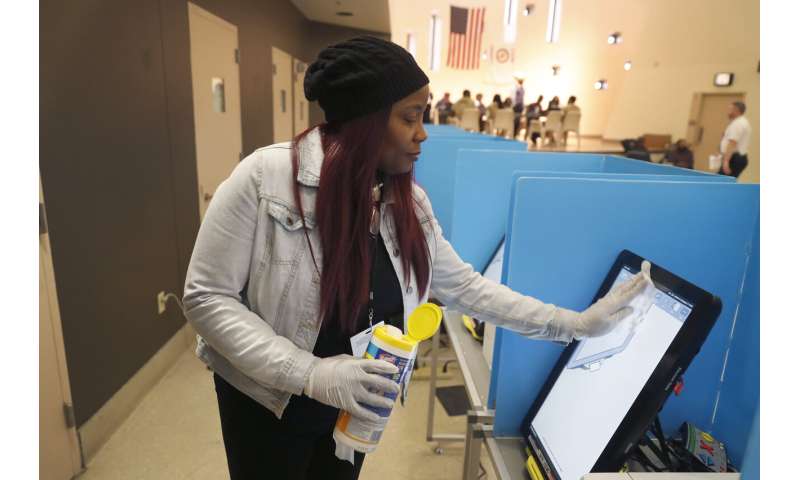

She is taking all the recommended precautions, she said, including washing her hands as soon as she finishes the class and wiping down the equipment before and after she uses it.

Seattle resident Marlena Blonsky said she wanted to help friends in need. The 33-year-old sustainability director at a Seattle logistics company has no children and has flexibility at work. She sent out a tweet Thursday that she was available for child care for her working-parent friends, or to run errands for those who have health problems and don’t want to go out in public.

Almost immediately, she had a taker and devoted a few hours last Thursday and Friday to watching a friend’s 3-year-old daughter. The child’s mother is a doctor who has long hours these days at work.

“I feel like this is hitting so many people harder than me, and this is the least I can do,” she said.

In New York, Bonita Labossiere toted a bag filled with toilet paper, snacks and a couple of bottles of pinot noir—the final touches on stocking-up she has done for three weeks.

The singer, voice teacher and director had no plans to flee New York, even as the outbreak grew more deadly there, having seen New Yorkers weather 9/11 and other frightening times.

Source: Read Full Article