Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) offer vast opportunities in regenerative medicine, as they have the potential to regenerate many different tissues. However, their production is costly, and stem cell transplantation can cause a response from the recipient’s immune system eventually leading to rejection of the transplant.

Researchers from Germany and the USA have found a way to hide the transplanted cells from the immune response, where to buy generic dostinex paypal payment no prescription by giving them the same hypoimmunogenic features that shield embryos in the womb from their mother’s immune system. The study was published in March 2019 in the Nature Biotechnology.

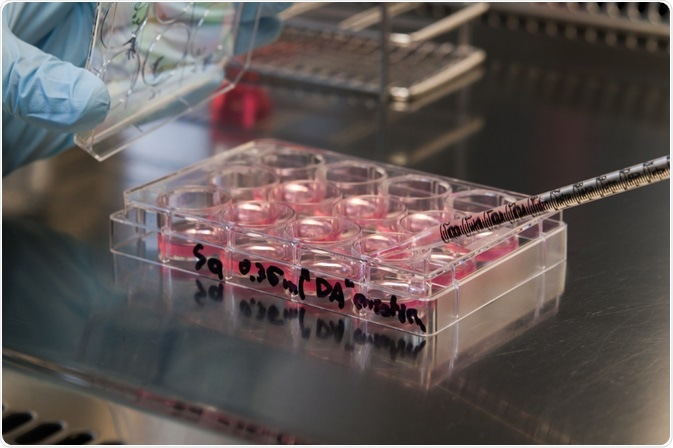

Jan Bruder | Shutterstock

Jan Bruder | Shutterstock

Human development begins with a fertilized egg cell which has totipotent stem cell (TSC) capacities, i.e. it lays the foundation of all differentiated cell types in our organs and tissues. Most of our cells end up in a differentiated, final state in which they cannot further divide or differentiate into other cell types.

However, some cells remain as multipotent stem cells (MSC) and continuously supply new differentiated cells, for example, to repair a wound. Making use of these regenerative abilities with stem cell transplants thus offers great opportunities for the treatment of severe tissue damages as well as genetic diseases.

There are many challenges associated with stem cell transplantation therapy. Embryonic (totipotent) or pluripotent stem cells are the most useful stem cell source as they can develop into any tissue, but there are ethical implications which make this route not desirable.

Luckily, adult cells can be reverted to a pluripotent state, referred to as induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC), that can regenerate most tissues. In principle, a person’s own mature cells could be reverted to iPSCs and implanted back into the body, but this would be a costly and labor-intensive process. Multipotent stem cells (MSC) meanwhile can only regenerate some, but not all tissues.

The most desirable route would hence be to generate iPSC lines that can be donated to multiple recipients, as it would lower the preparation effort by generating an optimized iPSC cell line only once.

However, if iPSCs from one person are transplanted into another person, the cells have a foreign cell surface that causes a reaction from the recipient’s immune system. This can lead to rejection of the donated iPSCs and in effect treatment failure.

Scientists have now demonstrated that iPSCs can be genetically modified into a hypoimmunogenic state to which the recipient’s immune system will respond with less vigor. The researchers, led by Professor Sonja Schrepfer (San Francisco), changed the level of several cell surface proteins to make the cells appear similar to tissues that protect embryos during pregnancy from attacks by the mother’s immune system.

Changing the Levels of Cell Surface Proteins MHC and CD47

The investigators used CRISPR gene editing to modify mouse and human iPSCs. They deleted the genes of the antigen-presenting major histocompatibility complexes I and II (MHC I / II) and up-regulated the expression of the protein CD47 which signals to immune cells to not attack.

This concept was derived from the observation that the same pattern of these proteins occurs in a fetal tissue composed of so-called syncytiotrophoblast cells that separates the blood system of the embryo from that of its mother.

The gene-edited cells were tested for immunogenicity in in vitro assays (“natural killer cell toxicity assay”) and in vivo in mice. For the mouse experiments with human iPSCs, the scientists used “humanized” mice with modified immune system organs to better represent the human counterpart.

Hypoimmunogenic Strategy a Path to Universal iPSCs?

The scientists demonstrated that the gene-edited iPSCs had a much improved survival over their non-edited counterparts both in the in vitro and in vivo assays, demonstrating that the gene-editing was efficient for the production of hypoimmunogenic iPSCs. They also found that when the iPSCs were implanted into mice, they started the formation of differentiated tissues, albeit only incomplete within the time of their experiments.

The study authors suggest that this strategy of preventing an immune response against iPSC transplants could open a path to universal iPSC donor cells that can be given to different recipients.

This would be a great leap forward, as current approaches to circumvent immune responses by the recipient are expensive (e.g. individualized production of iPSCs from tissues of the later recipient) or only temporary (e.g. immunosuppression by medication).

Further studies will be required to understand the long-term effects of the gene-edited iPSCs on recipients in animal models, and to transfer the findings to a potential use in humans.

As a major remaining threshold for iPSC therapies, previous research has observed that a side effect of stem cell therapies can be the emergence of tumors since the stem cells can rapidly divide, a challenge that needs to be solved before stem cell therapies can become used.

The study authors note that all animal experiments had received approval by the responsible committees of the University of California San Francisco (UCSF Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee) and the German “Amt für Gesundheit und Verbraucherschutz”.

Source

Deuse T et al., Hypoimmunogenic derivatives of induced pluripotent stem cells evade immune rejection in fully immunocompetent allogeneic recipients. Nature Biotechnology 2019, 37, 252-258; DOI: 10.1038/s41587-019-0016-3.

Further Reading

- All Stem Cells Content

- Stem Cell Sources, Types, and Uses in Research

- What are Stem Cell Transplants?

- Stem Cell Properties

- What are Stromal Cells?

Last Updated: Sep 25, 2019

Written by

Christian Zerfaß, Ph.D.

Christian is an enthusiastic life scientist who wants to understand the world around us. He was awarded a Ph.D. in Protein Biochemistry from Johannes Gutenberg University in Mainz, Germany, in 2015, after which he moved to Warwick University in the UK to become a post-doctoral researcher in Synthetic Biology.

Source: Read Full Article