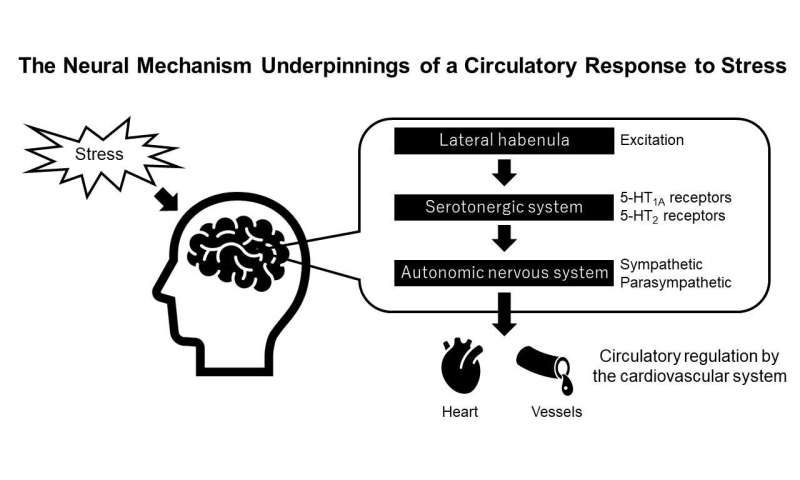

Although the heart beats autonomously, its function can be regulated by the brain in response to, for instance, stressful events. In a new study, researchers from the University of Tsukuba discovered a novel mechanism by which a specific part of the brain, the lateral habenula (LHb), regulates the cardiovascular system.

The cardiovascular system, specifically the heart and blood vessels, have a certain autonomy that allows them to function independently from the brain. In order for the individual to adapt to new, potentially threatening situations, the brain does have some regulatory power over the cardiovascular system. This is achieved by controlling the autonomic nervous system, which consists of the sympathetic and parasympathetic system. While the former has a stimulating effect on the cardiovascular system, including increasing the heart rate and blood pressure, the latter causes the opposite.

“From an evolutionary standpoint, the brain has had in incredibly important function in protecting the individual from predators,” says lead author of the study Professor Tadachika Koganezawa. “But even in the absence of predators, our bodies react to stressful situations. In this study, we wanted to determine how the brain regulated the cardiovascular system via the autonomic nervous system.”

To achieve their goal, the researchers focused on the LHb. Located deep within the brain, the LHb has been known to control behavioral responses to stressful events, and as such to elicit strong cardiovascular responses. However, the way in which it does so has remained unclear. To address this question, the researchers electrically stimulated the LHb in rats by inserting an electrode through the skull. Stimulation of the LHb resulted in bradycardia (low heart rate) and increased mean arterial pressure (MAP), which is a clinically useful parameter for assessing overall blood pressure.

To determine how the LHb interplays with the autonomic nervous system to regulate the cardiovascular system, the researchers then turned off the parasympathetic system by means of cutting the main parasympathetic nerve, the vagal nerve, or using a drug to antagonize it. While this suppressed the LHb’s effect on the heart rate, it did not change the MAP. Antagonizing the sympathetic system did the opposite—it decreased the MAP but did not change the heart rate.

To understand the mechanism by which the LHb elicits these cardiovascular responses, the researchers focused on the neurotransmitter serotonin, which plays an important role in the brain in modulating mood, cognition, and memory, among other functions. While blocking all serotonin receptors significantly reduced the LHb’s effect on both the MAP and heart rate, the researchers found that specific subtypes of serotonin receptors were particularly involved in the process.

Source: Read Full Article