Breast cancer, even at its initial stages, could be detected earlier and more accurately than current techniques using blood samples and a unique proteomics-based technology, according to findings of a study led by the Translational Genomics Research Institute (TGen), an affiliate of City of Hope.

Patrick Pirrotte, Ph.D., an Assistant Professor and Director of TGen’s Collaborative Center for Translational Mass Spectrometry, and an international team of researchers developed a test that can detect infinitesimally small breast cancer biomarkers that are shed into the bloodstream from cells surrounding cancer known as extracellular matrix (ECM), according to the findings of their study recently published in the scientific journal Breast Cancer Research.

For decades, physicians have relied on mammography breast imaging to look for cancer in a quest to provide prevention, early detection and reduce deaths. But the unintended consequences of both false positives and false negatives have off-set the hoped-for gains of this inexact type of screening, including complications from surgery and cardiovascular disease, and unnecessary biopsies of what turn out to be benign lesions.

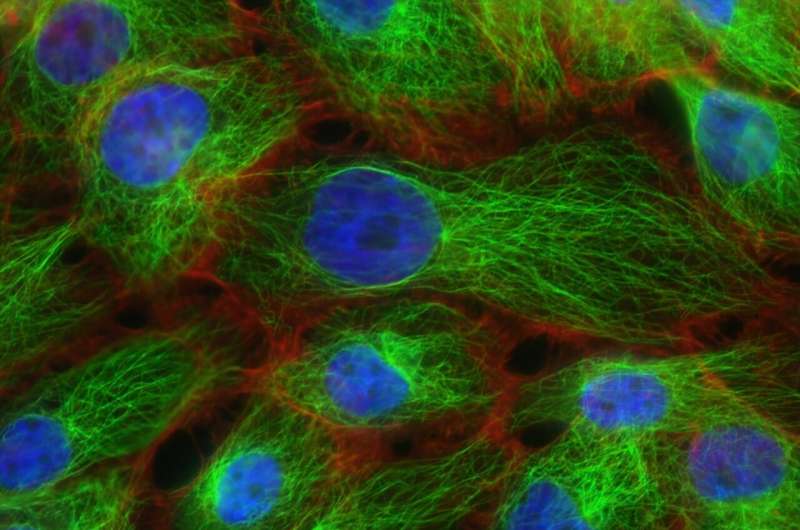

ECM is the network of molecules—including collagen, enzymes and glycoproteins—that provide structural and biochemical support to surrounding cells, including cancer cells. During the early stages of cancer, these proteins and protein fragments—which form the tumor microenvironment—leak into circulating blood.

“Our data reinforces the idea that this release of ECM components into circulation, even at the earliest stages of malignancy, can be used to design a specific and sensitive biomarker panel to improve detection of breast cancer,” said Dr. Pirrotte, the study’s senior author. “Using a highly specific and sensitive protein signature, we devised and verified a panel of blood-based biomarkers that could identify the earliest stages of breast cancer, and with no false positives.”

To establish this protein signature, researchers employed blood samples from 20 patients with IDC breast cancer, and from 20 women without cancer who nonetheless had positive mammograms but benign pathology at biopsy. These results were compared to five groups of individuals diagnosed with other cancers: ovarian, lung, prostate, colon and melanoma.

Because the number of ECM molecules in blood is relatively low, researchers relied on proteomics and new sample preparation enrichment techniques, including the use of hydrogel nanoparticles, to accurately detect cancer-associated biomarkers. This technique binds proteins from ECM associated with cancer proliferation, migration, adhesion and metastasis, or the spread of cancer from one part of the body to another. Many of these proteins had never before been observed in blood samples.

Source: Read Full Article