A “molecular volume knob” regulating electrical signals in the brain helps with learning and memory, according to a Dartmouth study.

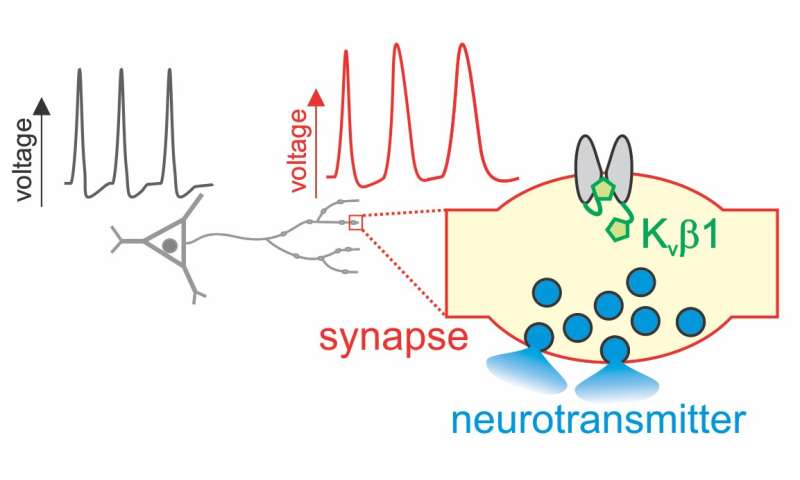

The molecular system controls the width of electrical signals that flow across synapses between neurons.

The finding of the control mechanism, and the identification of the molecule that regulates it, could help researchers in their search for ways to manage neurological disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease and epilepsy.

The research, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, describes the first study of how the shapes of electrical signals contribute to the functioning of synapses.

“The synapses in our brain are highly dynamic and speak in a range of whispers and shouts,” said Michael Hoppa, an assistant professor of biological sciences at Dartmouth and the research lead. “This finding puts us on a straighter path toward being able to cure stubborn neurological disorders.”

Synapses are tiny contact points that allow neurons in the brain to communicate at different frequencies. The brain converts electrical inputs from the neurons into chemical neurotransmitters that travel across these synaptic spaces.

The amount of neurotransmitter released changes the numbers and patterns of neurons activated within circuits of the brain. That reshaping of synaptic connection strength is how learning happens and how memories are formed.

Two functions support these processes of memory and learning. One, known as facilitation, is a series of increasingly rapid spikes that amplifies the signals that change a synapse’s shape. The other, depression, reduces the signals. Together, these two forms of plasticity keep the brain in balance and prevent neurological disorders such as seizures.

“As we age, its critical to be able to maintain strengthened synapses. We need a good balance of plasticity in our brain, but also stabilization of synaptic connections,” said Hoppa.

The research focused on the hippocampus, the center of the brain that is responsible for learning and memory.

In the study, the research team found that the electric spikes are delivered as analog signals whose shape impacts the magnitude of chemical neurotransmitter released across the synapses. This mechanism functions similar to a light dimmer with variable settings. Previous research considered the spikes to be delivered as a digital signal, more akin to a light switch that operates only in the “on” and “off” positions.

“The finding that these electric spikes are analog unlocks our understanding of how the brain works to form memory and learning,” said In Ha Cho, a postdoctoral fellow at Dartmouth and first author of the study. “The use of analog signals provides an easier pathway to modulate the strength of brain circuits.”

Nobel laureate Eric Kandel conducted work on the connection between learning and the change in shapes of electrical signals in marine sea slugs in 1970. The process was not thought to occur in the more complex synapses found in the mammalian brain at the time.

Beyond discovering that the electrical signals which flow across synapses in the brain’s hippocampus are analog, the Dartmouth research also identified the molecule that regulates the electrical signals.

The molecule—known as Kvβ1—was previously shown to regulate potassium currents, but was not known to have any role in the synapse controlling the shape of electrical signals. These findings help explain why loss of Kvβ1 molecules had previously been shown to negatively impact learning, memory and sleep in mice and fruit flies.

The research also reveals the processes that allow the brain to have such high computational power at such low energy. A single, analog electrical impulse can carry multi-bit information, allowing greater control with low frequency signals.

“This helps our understanding of how our brain is able to work at supercomputer levels with much lower rates of electrical impulses and the energy equivalent of a refrigerator light bulb. The more we learn about these levels of control, it helps us learn how our brains are so efficient,” said Hoppa.

For decades, researchers have searched for molecular regulators of synaptic plasticity by focusing on the molecular machinery of chemical release. Until now, measurements of the electrical pulses had been difficult to observe due to the small size of the nerve terminals.

The new research finding was enabled by technology developed at Dartmouth to measure voltage and neurotransmitter release with techniques using light to measure electrical signals in synaptic connections between neurons in the brain.

In future work, the team will seek to determine how the discovery relates to changes in brain metabolism that occur during aging and cause common neurological disorders.

Source: Read Full Article