Good nutrition is foundational to preventing chronic disease and helping people live a healthier life, and yet physicians responding to a Medscape Medical News survey said they believe that only about half of their patients would benefit from counseling on diet.

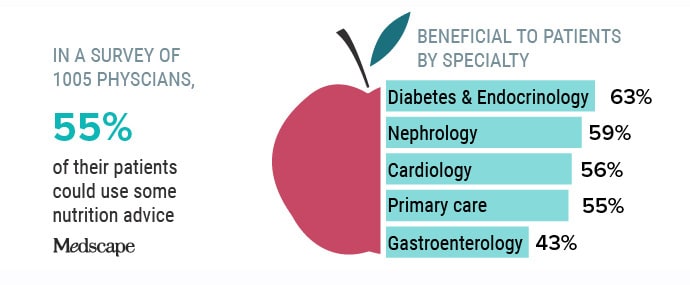

In the online survey of 1005 physicians, doctors said that 55% of their patients could use some nutrition advice. Broken down by specialty, diabetologists and endocrinologists said that 63% of their patients could benefit. By comparison, nephrologists said that 59% of their patients could use nutrition counseling. For cardiologists, it was 56%, for primary care physicians it was 55%, and gastroenterologists said that just 43% of their patients could benefit.

Those figures strike some specialists in obesity and preventive medicine as low.

“If the question is what percentage of patients could benefit from some nutritional guidance from a health professional, the true number is much higher than 55%; in fact, it’s 100%,” said Stephen Devries, MD, a preventive cardiologist and executive director of the educational nonprofit Gaples Institute in Deerfield, Illinois.

Devries notes that three quarters of US adults are overweight or have obesity, and at least 50% have prediabetes or diabetes, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Patients with other conditions — including hypertension, dyslipidemia, digestive disorders, and food allergies — could also benefit from discussions on nutrition, he said. “A meaningful discussion of nutrition needs to be included in the care of every patient,” said Devries, who is also adjunct associate professor at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Every single patient needs counseling because lack of good nutrition is “the basis of most of the chronic diseases that Americans and other people worldwide suffer from,” said Caroline Apovian, MD, co-director of the Center for Weight Management and Wellness in the Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Hypertension at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

“Everyone could benefit from nutritional counseling,” agreed Sylvia Bollie, MD, an integrative obesity specialist at Embrace You Weight and Wellness in Silver Spring, Maryland. “We should have at least a baseline of standard nutrition counseling or nutrition assessment for all patients, regardless of weight,” Bollie told Medscape.

Bollie said that the lack of proactive action on nutrition reflects the US “sick care” system, in which clinicians wait until a patient has an obesity-level body mass index (BMI) or out-of-control A1c before making a referral for a diet or lifestyle intervention.

Patients Not Seeking Advice?

Interestingly, the physicians surveyed by Medscape said that very few patients ask for nutrition advice. Endocrinologists said that one quarter of their patients seek diet counseling each month, whereas primary care physicians, nephrologists, and gastroenterologists said about 20% of their patients ask. Just 15% of cardiologists’ patients ask for nutrition advice in a typical month, according to the survey.

So why aren’t patients seeking that information from their physicians?

“It’s because they’re getting their nutrition advice on the street from…these random people on Instagram,” said Bollie. “They’re getting it from these noncredible sources because maybe they feel like the doctor doesn’t have time to talk to them about it, or the doctor doesn’t ask them about it, or the doctor doesn’t care.” They might even feel “that the doctor doesn’t know what they’re talking about,” she said.

Some patients might be reluctant because they believe that being overweight is their fault, said Apovian. “If most people don’t realize it’s a disease, then they’re not going to ask for help,” she said.

Devries said that surveys show that most patients want to receive information about nutrition and lifestyle from their doctor. But, he said, “If the physician doesn’t bring up the topic of nutrition, it’s understandable that patients come away thinking that diet must not be an important part of their care.”

Counseling Seen as a Priority, but Time a Factor

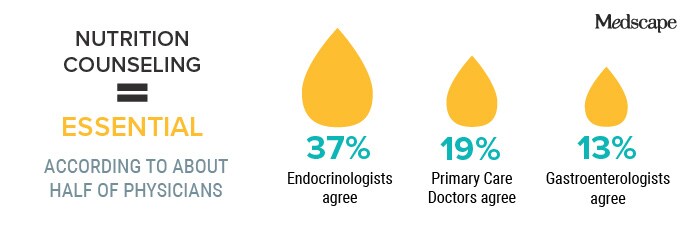

A little more than half of the physicians who responded to the survey said they viewed counseling on nutrition to be essential or a high priority. Broken down by specialty, endocrinologists were significantly more likely to label counseling as essential — 37%, compared with just 13% of gastroenterologists and 19% of primary care doctors.

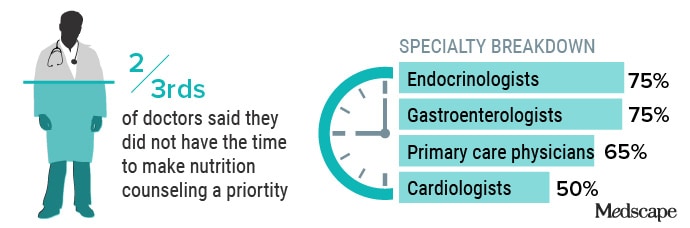

When asked why nutrition counseling is not a priority, two thirds of doctors said that they did not have the time. That was the top reason given by 75% of endocrinologists, 65% of primary care physicians, two thirds of gastroenterologists, and half of cardiologists.

“The time constraint issue is real, no doubt about that,” said Devries. But he said practices could have patients complete rapid dietary assessments in the waiting room, or a single diet-related topic could be discussed for a minute or two at each visit. At a minimum, physicians should make clear that “medication alone will never allow them to achieve their full potential for health without attention to diet and lifestyle,” he said.

Apovian agreed that time is a significant factor, especially for primary care doctors. They’re under financial pressure to meet blood glucose, blood pressure, and other targets and ensure that the patient has proper medications for diabetes and heart disease. But the same doctor “can let a patient walk out the door with a BMI of 45 and never discuss their weight” and “will not get dinged for it,” she said.

Doctors are “ill-equipped” to meet those targets because a 15-minute visit every 3 months is not going to allow enough time for prevention, said Bollie. “Even if I give you medicines, I’m just sprinkling a little bit of water on an oil fire,” because the fire is being fueled by a poor diet, she said.

Forty percent to 50% of specialists said that they did not make counseling a priority because they were concerned about lack of patient compliance.

But focusing on compliance is “short-sighted,” said Devries. He notes that only about half of patients given a statin are still taking them a year later. “We don’t turn around and say it’s pointless to prescribe statins,” he said. Believing that patients won’t make changes can become “a self-fulfilling prophecy,” said Devries.

Apovian calls the compliance factor “a misunderstanding of the disease.” Physicians should not think that “a patient with a BMI over 30 can actually stay on a diet and listen to the doctor and eat leafy green vegetables and chicken when everybody else around them is eating pizza.” Obesity is a complicated issue, she said.

Bollie agreed. “I can understand the frustration,” she said, adding that often, patients may not believe they have a weight problem or be ready to make a change, even if they have an A1C of 10.5. The reasons for not seeking or wanting advice are probably complex. A doctor might not be comfortable digging into those reasons, or it might take a referral to a therapist, she said.

Physicians should not make assumptions about who will follow nutrition advice, said Bollie. Many of those who are overweight or obese already face weight bias. And Black women — who are disproportionately obese — often face that bias on top of racism, she said. Assumptions could contribute to worsening health disparities, she said.

Only about one third of patients get counseling in-house, said survey respondents. This proportion was lower for cardiologists and gastroenterologists, who reported that only about 23% of their patients receive advice directly from them.

Overall, physicians referred about 16% of patients to diet and nutrition specialists, with nephrologists and primary care doctors referring slightly fewer. Endocrinologists had the highest referral rate, at 21%.

Most physicians said that they referred patients elsewhere because they believed that patients should have more dedicated care than they could provide. Other reasons included lack of time (cited by two thirds of specialists), and a lack of reimbursement (cited by 40% of nephrologists and one third of other specialists).

Referrals were also made because one third of specialists said they felt they had insufficient training on nutrition.

Lack of Training

Most survey respondents said that they had received scant nutrition training during undergraduate course work, medical school, and residency.

Those who had graduated within the past decade were more than twice as likely to have received nutrition coursework in medical school. Still, only 15% of those younger physicians said they had gotten that training.

Almost half of physicians working fewer than 10 years said that nutrition classes were required in medical school, compared with one third of those who had been in practice more than 30 years. Even so, two thirds said that their medical school nutrition training was inadequate or very inadequate.

Only about 19 hours is devoted to nutrition in medical school, said Devries. Although there are new classes on nutrition and culinary medicine being added, they are usually elective, he said. “Microbiology isn’t considered an elective in medical school, and neither should nutrition be,” he said.

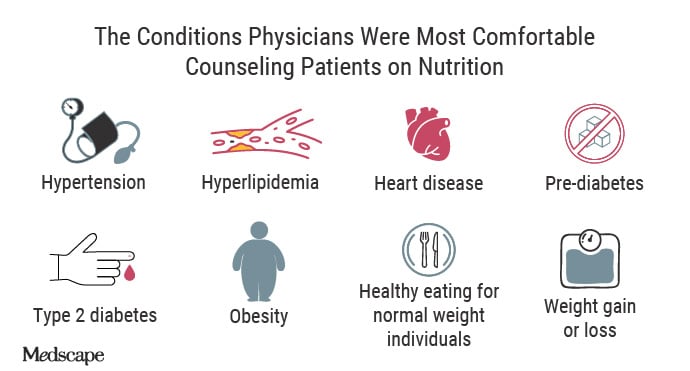

Just 38% of doctors said they were extremely or very knowledgeable about nutrition; half said they were somewhat knowledgeable. Overall, physicians were most comfortable counseling patients on nutrition for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, heart disease, prediabetes, type 2 diabetes, obesity, healthy eating for normal weight individuals, and weight gain or loss.

The comfort level dropped when it came to vitamin and mineral deficiencies, type 1 diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and pregnancy.

Half to two thirds of doctors had gleaned their nutrition knowledge through self-directed study or clinical practice. Endocrinologists were the most likely to say that they had learned in practice, whereas cardiologists were on the low end, stating that clinical practice had hardly contributed to their nutrition knowledge. Cardiologists and gastroenterologists were also less likely to say that they had engaged in self-directed study. Primary care physicians and endocrinologists said that studying on their own had a significant impact on their knowledge.

Bollie, who was previously a primary care physician, said that jibes with her own experience. “Most of what I’ve learned about nutrition has been through self-study or through my additional certification through the American Board of Obesity Medicine (ABOM),” she said.

Devries said that the Gaples Institute offers a 4-hour online course of nutrition essentials that emphasizes practical, clinical application. That course “is now required in the curriculum of several medical centers and has been taken by over 3000 medical students and practicing physicians,” he said.

Apovian — who also received advanced training through a one-year fellowship through the ABOM — has for three decades taught a nutrition and obesity medicine course for primary care physicians, first at Harvard and now through Dartmouth. Although thousands have taken the course, it’s still not enough, she said.

Her aim is to change the paradigm “to treat the obesity first with diet, exercise, and an anti-obesity medication, if diet doesn’t work,” she said. Because if the obesity is treated first, the patient might not need to progress to antihypertensives or diabetes medications, said Apovian.

But to get there requires an investment in talking to patients about nutrition, she said.

Devries is the salaried executive director of the Gaples Institute, an educational nonprofit that offers accredited continuing medical education courses for sale to health professionals. Courses are developed entirely through philanthropy to the Gaples Institute, a nonprofit that does not seek or receive corporate support. Devries does not receive royalties or personal consideration of any kind from the sale of these courses.

Alicia Ault is a Lutherville, Maryland-based freelance journalist whose work has appeared in publications including JAMA and Smithsonian.com. You can find her on Twitter @aliciaault.

For more news, follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube

Source: Read Full Article