A team led by researchers from the Yale School of Public Health has found how the B.1.1.7 variant of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), first found in the United Kingdom, made its way into several states in the United States. While the coronavirus pandemic has affected almost every country worldwide, the United States currently leads with over 27.8 million reported infections and the highest number of global deaths exceedingly over 2.4 million.

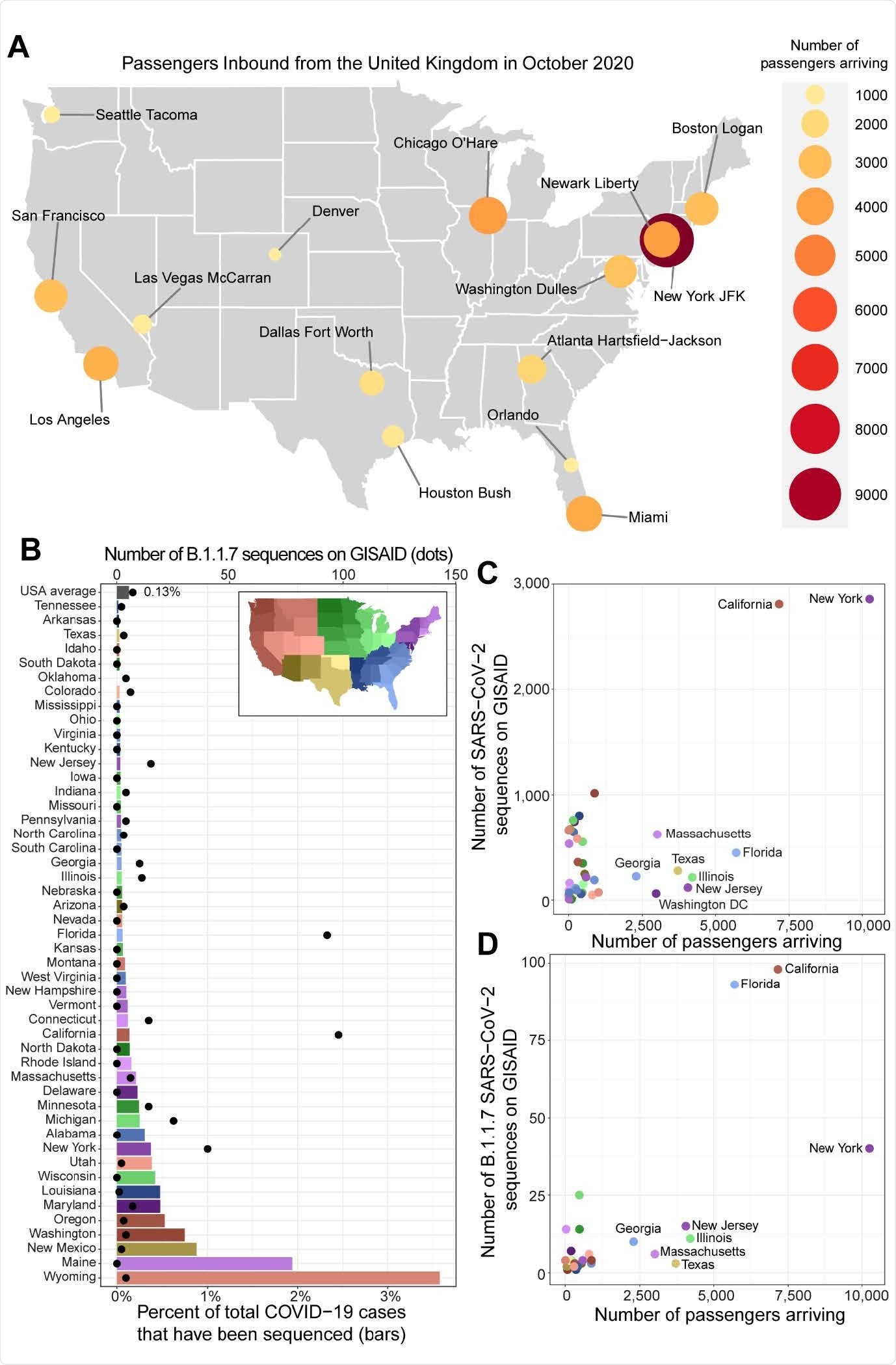

Kirsten St. George, Nathan D. Grubaugh and colleagues say that regardless of increased travel restrictions and increased coronavirus testing, the United States underreported genomic sequencing of potential new variants from confirmed positive COVID-19 cases. Because the United States sequenced only approximately 0.13% of COVID-19 cases, allied outdoor products it was initially difficult to detect when the B.1.1.7 variant first emerged in America.

“The sequencing capacity is highly variable across the country, and our travel data helps to identify regions disproportionately underreporting cases of B.1.1.7 and where it would be prudent to immediately prioritize variant surveillance,” write the authors.

The study “Early introductions and community transmission of SARS-CoV-2 variant B.1.1.7 in the United States” is available as a preprint on the medRxiv* server, while the article undergoes peer review.

Tracking down the virus

The researchers used a combination of October 2020 flight records from the United Kingdom into all United States airports and SARS-CoV-2 genomic sequencing to detect the origins of the B.1.1.7 variant in the U.S. They reasoned this time period was chosen because not only was it the most recent data available, but it also overlapped with the time the B.1.1.7 variant was initially thought to have been spreading all over the United Kingdom.

According to the CDC’s early February report, 33 states have confirmed 541 B.1.1.7 cases in the United States. However, the authors reason the low genomic surveillance may not represent the true extent of the variant’s spread. They instead analyzed the number of reported cases from December 2020 to January 2021 with the percent of SARS-CoV-2 clinical samples taken.

Strong evidence of variant spread first originating in New York

Low genomic surveillance was reported from December to January, with only 0.1% of COVID-19 cases sequenced and made available to researchers. A total of 26 states had less than 0.1% case sequences, and at the time of preprint publication, 14 states had not submitted any genomic sequence related to B.1.1.7.

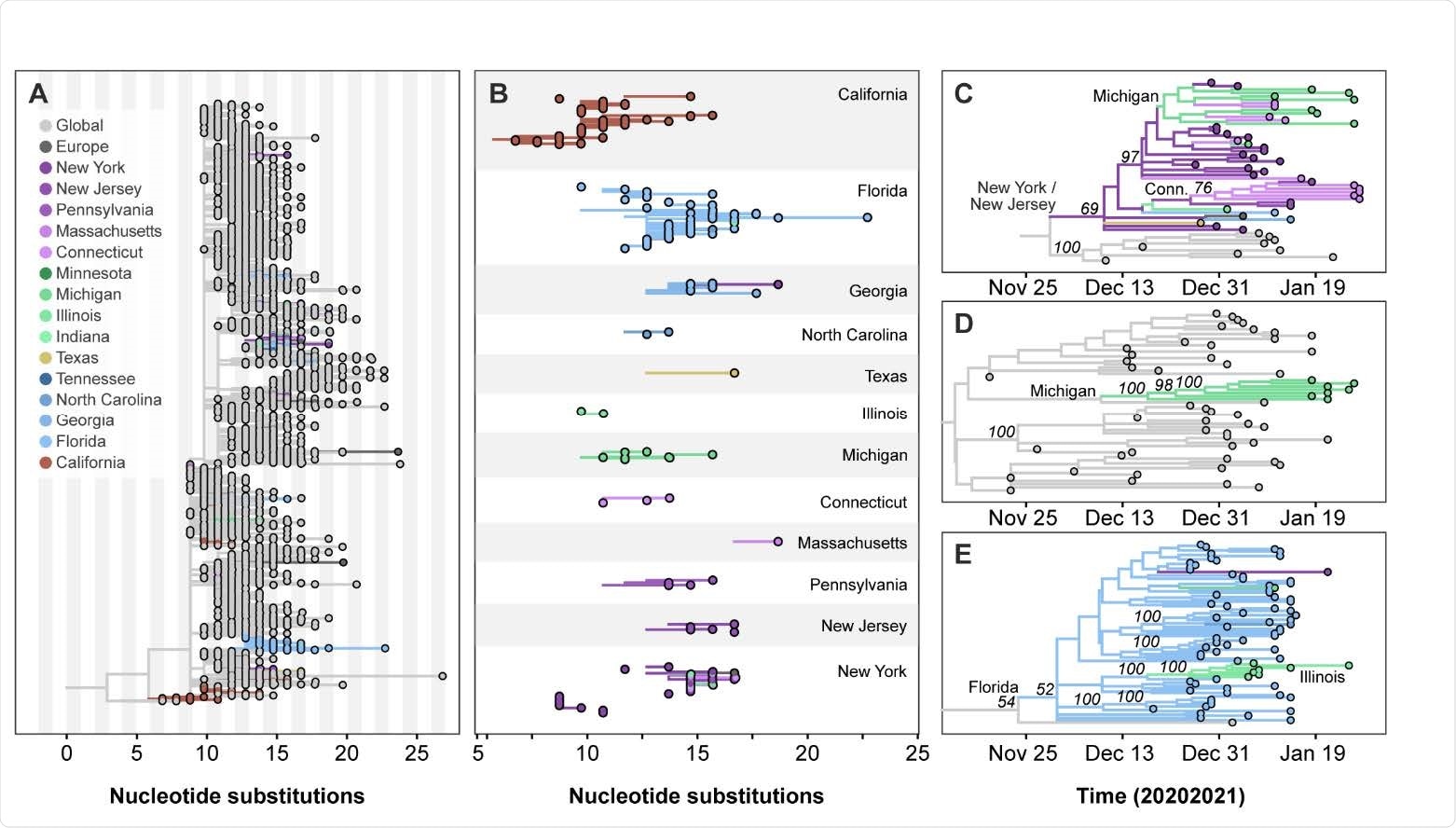

A high number of B.1.1.7 strains were found in New York, California, and Florida. The sequencing coincides with the large number of incoming international flights from the United Kingdom into these states’ airports.

Of all three, the researchers concluded that New York most likely was the central hub for incoming B.1.1.7 variants, which later spread to other states. The New York-New Jersey area had a record of 14,317 passengers to and from the United Kingdom. These results correspond with the first COVID-19 case with the new variant detected in New York’s Saratoga County on December 24, 2020.

As the B.1.1.7 variant remained undetected, the researchers suggest sustained community transmission likely occurred in New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, and Illinois starting January 2021.

“Thus, increasing surveillance for B.1.1.7 and other variants through sequencing and more conventional methods must be made a high priority,” write the researchers.

Strong possibility of B.1.17 variant in other states

While the researchers sequenced most B.1.1.7 variants in New York, the researchers say underreporting may have contributed to undetected cases in other states. Their results showed Texas, Illinois, and New Jersey had more than 2,500 people flying in from the United Kingdom. Yet, all three states had 0.05% or less of sequenced cases. The authors suggest a strong possibility that the spread of the new strain is increasing in other states.

“In places like New Jersey, Illinois, and Texas, however, if SARS-CoV-2 genomic surveillance could be increased, it might determine if B.1.1.7 cases are disproportionately underreported as compared to New York and California,” write the researchers.

More genomic surveillance needed for future research

Given the limited travel data and low genomic surveillance, the researchers say it’s too small of a sample to represent the entire spread of this variant in the United States. Additionally, they could not evaluate the rate of transmission across different regions and assumed community spread was high. “In reality, local conditions and behaviors play an important role for B.1.1.7 establishment, and could explain why cases are low in some states.”

With the rising spread of the new variants, the research team suggests increasing genomic surveillance is a high-priority task needed to mitigate the virus’s spread.

*Important Notice

medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

- Alpert T, et al. Early introductions and community transmission of SARS-CoV-2 variant B.1.1.7 in the United States. medRxiv, 2021. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.10.21251540, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.02.10.21251540v2

Posted in: Medical Research News | Disease/Infection News

Tags: Coronavirus, Coronavirus Disease COVID-19, Genomic, Genomic Sequencing, Pandemic, Phylogeny, Public Health, Research, Respiratory, SARS, SARS-CoV-2, Severe Acute Respiratory, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, Syndrome, Virus

Written by

Jocelyn Solis-Moreira

Jocelyn Solis-Moreira graduated with a Bachelor's in Integrative Neuroscience, where she then pursued graduate research looking at the long-term effects of adolescent binge drinking on the brain's neurochemistry in adulthood.

Source: Read Full Article