This weekend, participants in the Kokoda Challenge will complete a grueling 96-kilometer overnight trek to raise money for youth programs.

And every year, thousands of Australians undertake long-distance runs or challenging bike rides, go a month without booze, shave their heads, sleep outdoors or grow an unflattering mustache—all in the name of charity.

Why are people willing to go to such extremes of pain, effort and embarrassment to raise money for a charity? Wouldn’t it be easier simply to donate, and ask their friends to do likewise?

Humans are primarily driven to seek positive and pleasurable experiences, and to avoid negative ones such as pain and effort. But research shows that the prospect of enduring pain and suffering for a charity can raise up to three times as much money.

How many times have you been approached in the street by a charity worker seeking donations for a worthy cause? If you decide you want to donate, the process is almost effortless: just tap ‘n’ go. But there are many different worthy causes vying for donations.

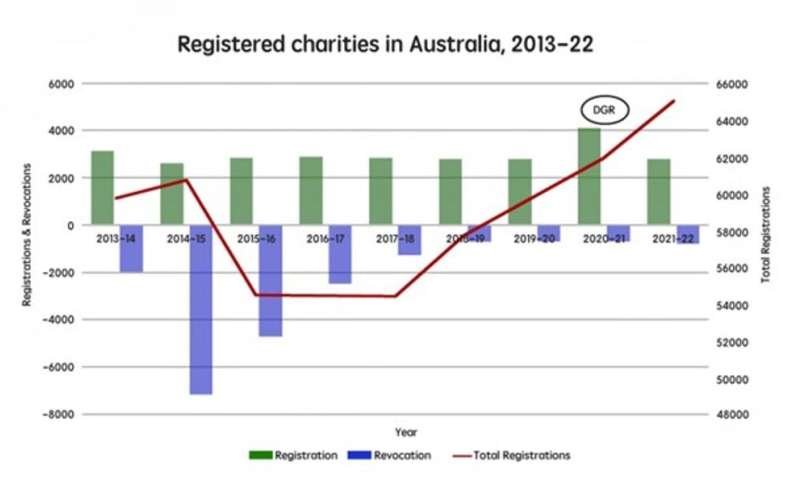

By the end of 2021, Australia will have around 65,000 registered charities. The figure is growing at 4% each year—much faster than the overall population, which means the competition will only get fiercer.

How can charities make themselves stand out from the crowd and ensure your donation goes to them, rather than someone else equally deserving?

No pain, no gain

Home shopping networks routinely promote “revolutionary” exercise equipment that promises to flatten your stomach or improve your circulation with ease.

But research shows we’re highly skeptical of these claims. We know there’s no real gain without pain, and we’re inclined to disbelieve anyone who tells us the opposite.

People also believe this to be true of education, career advancement, sporting performance and even shopping.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=873ZKrxB444%3Fcolor%3Dwhite

And when it comes to charity, this explains why we feel we need to do more than just donate $20 to make a significant and positive change to a worthy cause.

This is the suggested logic behind the “martyrdom effect”: the idea that the mere prospect of being in pain can promote charitable giving.

This effect was demonstrated in a series of five experiments by Christopher Olivola at the University of Warwick and Eldar Shafir at Princeton University.

In the first experiment, respondents were asked how much they would pay to take part in one of two hypothetical charity events: a picnic fundraiser, or a five-mile run. Participants who chose the charity run intended to donate US$23.87—almost twice as much as those who chose the picnic, who were willing to stump up US$13.88.

In a second experiment, the researchers replaced the hypothetical events with real money and real pain. Each participant was given $5 to divide between themselves and a donation to a public pool. But some participants were told their public donation would be doubled if they chose to place their hands in very cold water for one minute.

Participants who opted to endure the pain were willing to donate nearly 25% more of their $5 than those who chose to avoid the discomfort.

More miles, more money?

If a friend is running a marathon, we might typically sponsor them a dollar a mile. So do longer feats of endurance earn more money? Well, yes, but it’s not quite as straightforward as that.

In their third experiment, the researchers investigated this idea by asking participants to choose a distance between 1 and 20 miles, and asking how much they would pay to participate in a charity run of that length.

Strangely, there was no significant correlation between distance and the amount donated. But participants did rate longer runs as involving more pain and effort. And this was the crucial factor that determined the size of their donations.

Put simply, you have to run far enough to genuinely suffer before it starts being worth more money.

The meaningfulness of martyrdom

As noted above, people consider “meaningful” goals (a better physique, career progression, higher education) more worthy of pursuit and reward than easier (and presumably less meaningful) goals.

In the next experiment, which was similar to experiment 1, British participants were asked how much they would be willing to pay to take part in a charity fundraiser that was either grueling (a five-mile run) or enjoyable (a picnic). What’s more, they also reported how meaningful the experience of participating and the act of giving would be to them.

Participants considered the charity run significantly more meaningful, and offered to donate almost three times more than picnic participants: £17.95 versus £5.74.

The cause makes a difference

Not all charities raise funds for human suffering, disease or natural disasters. Many support art galleries, childrens’ sporting equipment or parks.

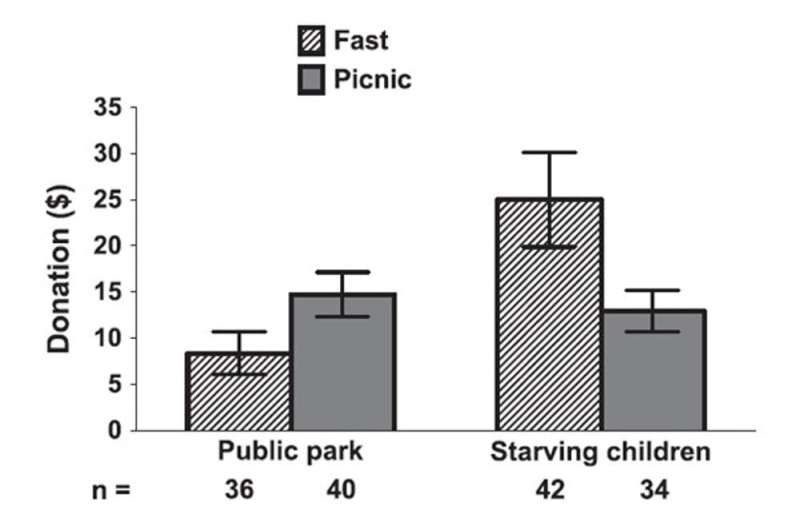

In a final experiment, participants were presented with two new causes (helping starving children versus funding a public park) and two ways to support (fasting versus hosting a picnic). Here are the results.

When the cause involved human enjoyment (a new park), participants were more likely to choose the “easy” option (the picnic) and to donate more to that than to a fast in support of the new park. In contrast, if the cause aims to alleviate human suffering (by feeding starving children), participants were more inclined to donate money to the “hard” option (fasting) than to a charity picnic.

This underscores the importance of a good “fit” between the event and the cause—something corporate advertisers already understand. It shows why cigarette companies, for example, were always an uncomfortable fit for sponsoring sporting events.

Source: Read Full Article