insights from industryDr. Ron DanielsFounder and Chief ExecutiveUK Sepsis Trust

insights from industryDr. Ron DanielsFounder and Chief ExecutiveUK Sepsis TrustIn this interview, News-Medical talks to Dr. Ron Daniels about his work at the UK Sepsis Trust, the impacts of the antimicrobial resistance crisis on sepsis, and why urgent action needs to be taken.

Please can you introduce yourself and tell us about your role at UK Sepsis Trust?

My name is Dr. Ron Daniels. I am an intensive care consultant in Birmingham in the West Midlands, England, and the founder and chief executive of the UK Sepsis Trust.

Every three seconds someone in the world dies from sepsis. Please can you tell us more about what sepsis is and why it is so deadly?

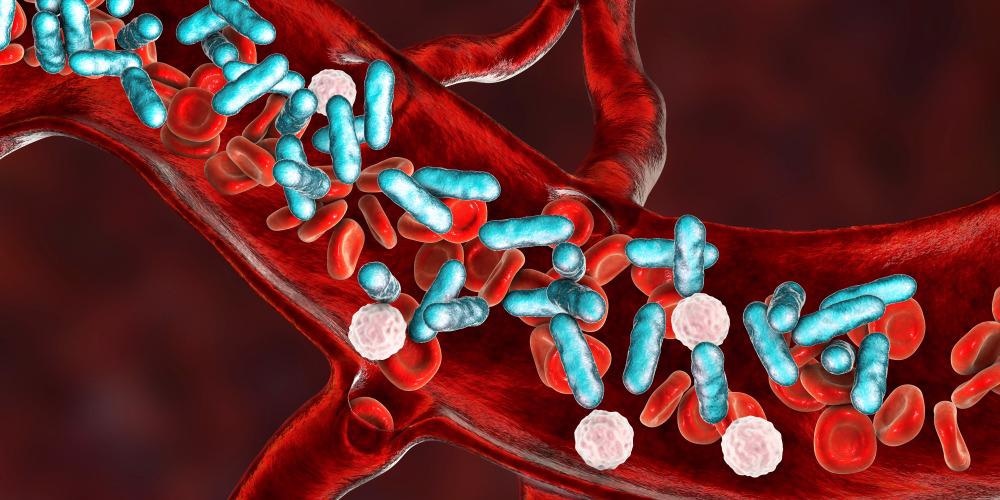

Sepsis is the way the body responds to an infection. It is always triggered by an infection, which can be anything from pneumonia or a urinary infection, to a problem in the tummy, to something as simple as a cut, bite or sting. In sepsis, the body's immune system overreacts and goes into overdrive. If we do not control that process, then it starts to cause organ damage which can lead to death.

Sepsis. Image Credit: Kateryna Kon/Shutterstock.com

The UK Sepsis Trust is helping to fight this life-threatening condition. What are some of the aims and missions of the UK Sepsis Trust?

Our overarching mission at the UK Sepsis Trust is to prevent avoidable deaths from sepsis and to improve the outcomes for those who survive the condition. Getting this right demands a system-wide approach.

One thing we certainly do is work with health professionals, educate them, and provide them with the clinical solutions to help them deliver the very best care to their patients presenting with sepsis in an often chaotic setting.

But on its own, that is not enough. Patients all too frequently present too late because they do not know when to access healthcare or when they are deteriorating from an infection. So another important aspect of what we do is raising public awareness to ensure that more people access healthcare at the right time.

Once this has happened, people have accessed healthcare and health professionals have done the right thing, the third area involved is support for those who have gone through this process. Some of them will very sadly be families who have been bereaved and are left asking why. But we also support and empower survivors because the road to recovery from sepsis is measured in months rather than weeks, and people need support in their psychological recovery, their physical recovery and also in the cognitive space.

You recently said that the UK's approach to tackling superbugs is outdated. Why is this and what do you believe governments, policymakers and organizations should be doing to create change in the way that we treat deadly conditions such as sepsis?

So I have two issues really with the way not just the UK government, but many governments approach the problem of antimicrobial resistance and superbugs. The first is that we have surveillance for diseases, which is based upon individual bugs; we call them pathogens and they will mostly be bacteria, but of course, viruses and fungi as well.

Governments often have laboratory-based clinicians who are exercising their clinical skills day in, day out, identifying and counting these bugs. But that on its own is not enough, because all too often, our diagnostic systems fail to identify the bug.

For many people who suffer sepsis, we never identify the bug that is causing it. However, we still need to track those patients and understand what is happening to them, how they are recovering, and whether we can improve on that.

The second issue is the public messaging around superbugs. In the UK, Dame Sally Davies has achieved probably more than any other individual in the world in raising the profile of antimicrobial resistance at a policy level and I think humankind needs to thank her for that. But there have been some areas in which I feel the public messaging could be improved.

The messaging has suggested to people that if we do not act now on antimicrobial resistance, we might find ourselves in a situation in several decades where we cannot safely undertake elective surgery because of the risk of untreatable infection. That is not enough.

This needs to be immediate and this needs to be personal because right now in my hospital, I have got people with very resistant bugs. Antimicrobial resistance is here today, and I think we need to be much better at communicating that public message.

Several years ago now, Lord O'Neil wrote a seminal report for the British government on antimicrobial resistance. One of the headline statements was that if we do not act now on antimicrobial resistance, by 2050 we will see an extra 10 million lives lost every year. I believe Lord O'Neil was being optimistic actually. I believe that 10 million is the lower end of the likely risk.

With the rate at which antimicrobial resistance is marching forward, if we do not act right now it will become a very real problem by 2050. At the moment, 49 million people around the world suffer sepsis and we lose 11 million of those people. But if we do not have effective antibiotics, by as early as 2050 we will see every one of those 49 million people dying because the infection causing sepsis will be untreatable. That extra 38 million lives lost every year will tip the balance between human population growth and human population decline. So when people talk about this being existential, they are not exaggerating.

Antibiotics. Image Credit: Fahroni/Shutterstock.com

Antibiotic resistance is a global health crisis. What impact is antibiotic resistance having on sepsis and why is it important to help raise awareness surrounding the importance of antibiotics and their safe use?

Very recently, the World Health Organization highlighted a report that showed that last year, at the time of writing, an estimated 1.3 million people died around the world as a consequence of antibiotic resistance. Now, of course, antibiotic resistance per se is not what is causing death. What is causing death is infection that is untreatable, and antibiotic resistance is a driver towards that.

This is real and this is today. In hospitals up and down the United Kingdom, and in every country in the world, there are people right now in whom the initial antibiotic therapy is ineffective because the bugs are already resistant. So if it was 1.3 million last year, it is going to be more than that this year. If we look ahead just a decade, we can expect to see that to increase exponentially. The time to act is right now.

Recently you have joined a coalition called the Infection Management Coalition, along with members such as Antibiotic Research UK, Pfizer, and Thermo Fisher Scientific, to demand change in how infections are detected, monitored, prevented, and managed across NHS. Could you tell us a bit more about this coalition and what it is trying to achieve?

The Infection Management Coalition is almost unique. It is the first time in this sector that stakeholders from industry have come together with industry regulatory bodies, advocacy organizations, key opinion leaders, and professional societies to deliver one message.

The principles behind the Infection Management Coalition cover 29 recommendations, but the key message is that at a policy level, we need to consider infection management holistically. We should not have a situation where a government is producing an antimicrobial resistance strategy and a different sector of government is producing a sepsis action plan.

There are four pillars of infection management:

- Number one, which is obviously very topical now, is outbreak surveillance and pandemic preparedness.

- Number two is infection prevention and control, which of course includes vaccination strategies, but also includes access to resilient healthcare systems, clean water, sanitation and hygiene.

- Number three is antimicrobial stewardship in all its forms. That is, improving the behavior of the public and clinicians with regards to prescribing and accessing antimicrobials, but also around the antimicrobial pipeline and examining whether we can improve and reduce their use in other industries, such as in intensive farming.

- The fourth area is the rapid treatment of time-critical infection, including sepsis, because that is what the other three exist for. This is about saving lives from infection and ensuring we have the armamentarium to do that in a few decades.

Health professionals have a healthy and appropriate skepticism about industry and the motives for industry becoming involved in projects like this. But at the end of the day, this is so big. This is bigger than health professionals. This is bigger than individual professional societies. We have got to work together.

On your site, you also offer support for survivors and relatives, as well as advice on dealing with bereavement. How important is this communication with patients and their families to UK Sepsis Trust?

It is hugely important. If a loved one went into hospital with a heart attack or a stroke, you would rightly and reasonably expect that they would come out with a package of rehabilitation. They would see a physiotherapist, a cardiologist and a stroke physician. As a loved one, you would expect that.

With sepsis, it is very different because sepsis does not belong to a particular specialty in hospitals. Often these people have been through intensive care and there is no follow-up service, let alone rehabilitation for people who have survived an intensive care stay with sepsis.

Now, why is this a problem? It is because 40% of people who survive sepsis still have problems one year after their illness. These can be physical, ranging from relatively minor problems such as easy fatigue or muscle pain, to disabling fatigue, disabling pain syndromes, and even limb loss.

They can also be psychological, which again can vary from relatively mild sleep disturbances or the occasional controllable panic attack, right through to posttraumatic stress disorder in about a fifth of survivors.

Then there is the cognitive space. We have heard about this in the context of COVID-19 and the public has described it as brain fog. This was no surprise to those of us that have been in the sepsis recovery space for some time because 17% of people who survive sepsis have moderate to severe cognitive dysfunction. They cannot think as clearly. And so they need support. Our support nurses are a lifeline to these patients and to their families.

Not only are they asking “why”, “is it just me”, and “is this ever going to get better?”, but they also need to know how to communicate this to their employers and broader family who are all expecting them to bounce back to normal very quickly. The reality is very different.

As well as offering support for survivors and their families, you also offer professional resources for the healthcare community. What kind of resources can healthcare professionals find on your site and why is providing access to these resources critical in helping to aid early diagnosis?

At the Sepsis Trust, we see our role and our USP as translational work. There are multiple academic societies producing guidelines. There are an international set of guidelines from the Surviving Sepsis Campaign. As we record/write this, the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges in the UK is about to release guidelines for the national practice.

Those academic guidelines are hugely important, but what we also need is some operational solutions for frontline health professionals. The guidance is typically lengthy and verbose. It contains a lot of context and explanation, but that does not help a busy health professional who is faced with 30 or 40 undifferentiated patients with different medical conditions. What they need is something easy to access and easy to deliver.

We will be translating the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges' work into two side proformas for junior health professionals to use at the bedside. They include the recognition strategy to help them to treat patients with sepsis rapidly, which we call Red Flag Sepsis, together with the treatment strategy, which is a bundle of care we have been using for the last 16 years in the UK called the Sepsis Six.

Each of these will iterate slightly with the new guidance, but they are there as tools to communicate to health professionals what they need to do right now rather than what they can do when they have got several hours of bedtime reading time available.

When we had a resolution on sepsis adopted by the World Health Organization, we asked the former Chief Medical Officer, Sir Liam Donaldson, to write a forward to the publication. And he said some very important clinical issues, some of them a matter of life and death, exist in a backwater inhabited by academics and enthusiasts and professionals. But the reality is that these need to be in the public and political space in order for things to change on a large scale. That is where we see our role.

What is next for UK Sepsis Trust? Are you involved in any exciting upcoming projects?

As we speak, we are entering our 10th anniversary of the inception of the Sepsis Trust. We have achieved a huge amount in those 10 years. We have taken sepsis from a condition that was barely known by the public or considered by anyone other than a handful of health professionals, to something mainstream that the public is increasingly aware of. I think we need to celebrate that.

But now we have to transition. We have to recognize that with that success comes responsibility. And historically we have been really quite didactic around telling junior health professionals what to do, encouraging them to act rapidly, including the delivery of antibiotics.

We now have to subtly migrate that messaging to one of greater responsibility. We need to accept this new landscape where most people in the health professions are aware of sepsis and ensure that they deliver the right sepsis care to the right patient, but without the adverse consequence of excessive use of antibiotics.

The Infection Management Coalition, to which we proposed and hold a collaborative secretariat, is an important stepping stone toward that. We have now got to ensure that health professionals do not lose their level of alertness regarding sepsis and do not treat people with other conditions as if they might have sepsis just in case.

About Dr. Ron Daniels

Ron Daniels is an NHS Consultant in Intensive Care, based at University Hospitals Birmingham, U.K. He’s also Chief Executive of the UK Sepsis Trust and Vice-President of the Global Sepsis Alliance. In 2016 he was awarded the British Empire Medal for services to patients.

Ron’s expertise lies in translational medicine and leadership. He leads the team driving dissemination of the Sepsis 6 treatment pathway and is part of the team responsible for much of the policy and media engagement around sepsis in the U.K. and elsewhere, including as a core member of the team securing the adoption of the 2017 Resolution on Sepsis by the WHO.

At home, Ron’s worked with the NHS over the last 7 years to ensure that, in England, more than 80% of patients presenting with suspected sepsis now receive appropriate antimicrobials rapidly. He’s ever mindful of the perceived conflict, and the synergies and need for collaboration, with the antimicrobial stewardship agenda.

Posted in: Thought Leaders | Medical Science News | Medical Condition News | Disease/Infection News

Tags: Antibiotic, Antibiotic Resistance, Antimicrobial Resistance, Bacteria, Brain, Brain Fog, covid-19, Diagnostic, Elective Surgery, Fatigue, fungi, Global Health, Healthcare, Heart, Heart Attack, Hospital, Hygiene, Immune System, Intensive Care, Laboratory, Muscle, Pain, Pandemic, Panic Attack, Pneumonia, Research, Sepsis, Sleep, Stress, Stroke, Surgery

.png)

Written by

Emily Henderson

During her time at AZoNetwork, Emily has interviewed over 200 leading experts in all areas of science and healthcare including the World Health Organization and the United Nations. She loves being at the forefront of exciting new research and sharing science stories with thought leaders all over the world.

Source: Read Full Article