When the United States suffered a great wave of smallpox outbreaks at the turn of the 20th century, the public health field was in its infancy.

Compulsory vaccinations were haphazard and often discriminatory. Many people did not trust the vaccines or the local governments doing the vaccinating. At the time, the federal government passing nationwide vaccination measures would have been unthinkable.

The events of this time, known as the Progressive Era, paved the way for laws and regulations still in force today. Michael Willrich, the Leff Families Professor of History, chronicled this period in American history in his award-winning book, “Pox: An American History.” If widespread distrust of public officials and discrminiation against marginalized groups during the smallpox outbreaks made containing the virus difficult, the development of sound public health practices at the time finally defeated the epidemics.

Willrich took some time to discuss the outbreaks and their relevance to today’s COVID-19 pandemic with BrandeisNow.

What are some of the laws and rules established during the smallpox outbreaks of the early 20th century that still apply today?

Willrich: In the wake of the smallpox epidemics of the late 19th and early 20th century and the controversies they generated, Congress enacted what was called the Biologics Control Act, which lay the foundation for the vaccine safety regulations that are still in effect today. It established a new system of federal licensing and regulation of vaccine production, ultimately leading to safer production and more effective vaccines, and it paved the way for greater regulation later in the century.

What role did the U.S. Supreme Court play?

Willrich: In 1905 the Court ruled on the constitutionality of compulsory vaccination measures in Jacobson vs. Massachusetts. In upholding the legitimacy of compulsory vaccination, the Supreme Court compared the right to enact public health measures during an epidemic to the right of a government, any government, to defend its people from a military invasion. And they compared the right to compel individuals to be vaccinated, whether they wanted to or not, to the power to conscript the people in order to raise an army. These are very strong statements of public health authority.

However, the Court emphasized that these measures must not be arbitrary and unreasonable, that they must address legitimate public health concerns, and that in some extreme cases public health regulations might be “so arbitrary and oppressive” as to justify judicial review. That is an important standard, and Jacobson remains the major case today in public health law, more than a century later.

Why was there resistance to compulsory vaccination during these outbreaks?

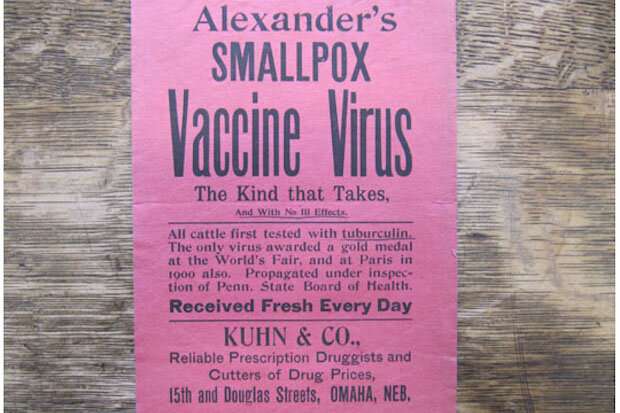

Willrich: The smallpox vaccine had been around for more than a century by this time, but vaccines were mostly produced by unregulated commercial enterprises. The governments were compelling people to get vaccinated, but those same governments were not regulating vaccine production to ensure that vaccines were safe and effective.

In the U.S., the vaccines on the market in the early 20th century were mixed in terms of quality and safety. Some of them were connected to tetanus outbreaks, such as in 1901 in Camden, New Jersey, when nine school children died of tetanus following a compulsory vaccination order. So there were concerns about vaccine hazards that were not negligible.

Also at this time, there was no workman’s compensation. Ordinary working people could expect to be sick for a few days, to have sore arms, to be unable to go to work for a couple of days after vaccination, and this was considered a violation of their right to support their families.

Then there were groups of people with reasons to harbor opposition. African Americans had really good reasons to be suspicious of white health officials; they had been subject to a kind of Jim Crow medicine for years. Christian scientists and other faith groups that believed in either natural healing or community or individual control over health decisions had strong opposition.

How were public health measures determined and carried out?

Willrich: Public health measures then were almost entirely the province of state and local governments. The vaccine orders were being carried out by local boards of health or state law, under what was known as the police powers—a reservoir of powers going back to the Anglo-American common law that gave governments the authority to interfere with individual liberty or property rights in the name of the general welfare and the public well-being.

How was compulsory vaccination carried out in discriminatory ways?

Willrich: Ultimately, compulsory vaccination was carried out in many communities in a way that was discriminatory against African Americans and immigrant groups. There were examples of compulsory vaccination being carried out with force in immigrant tenement districts in cities like Chicago, New York and Boston. Local governments created “virus squads,” teams of police and vaccinators that cordoned off city blocks, entered neighborhoods in the middle of the night, and went door to door, checking people to see if they had vaccination scars proving they had recently been vaccinated. Police tore infected children from their mothers’ arms and took them to isolation hospitals called “pesthouses.”

What was the role of the federal government during these epidemics?

Willrich: It was very different from today, where people are looking to the White House for leadership. Even in the era of Teddy Roosevelt, who was the president during these smallpox epidemics, very few people looked to the president for leadership on how to fight a disease. This was before the extraordinary growth of the federal government in the 20th century. At the time, it would have been really foreign to the way of American thinking about politics and government to have the federal government passing nationwide vaccination measures.

What do the smallpox epidemics have to teach us about defeating COVID-19 today?

Source: Read Full Article