What is Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection (SCAD)?

The epidemiology of SCAD

Pathogenesis and pathophysiology of SCAD

Clinical presentation of SCAD

Managing SCAD

References

Further reading

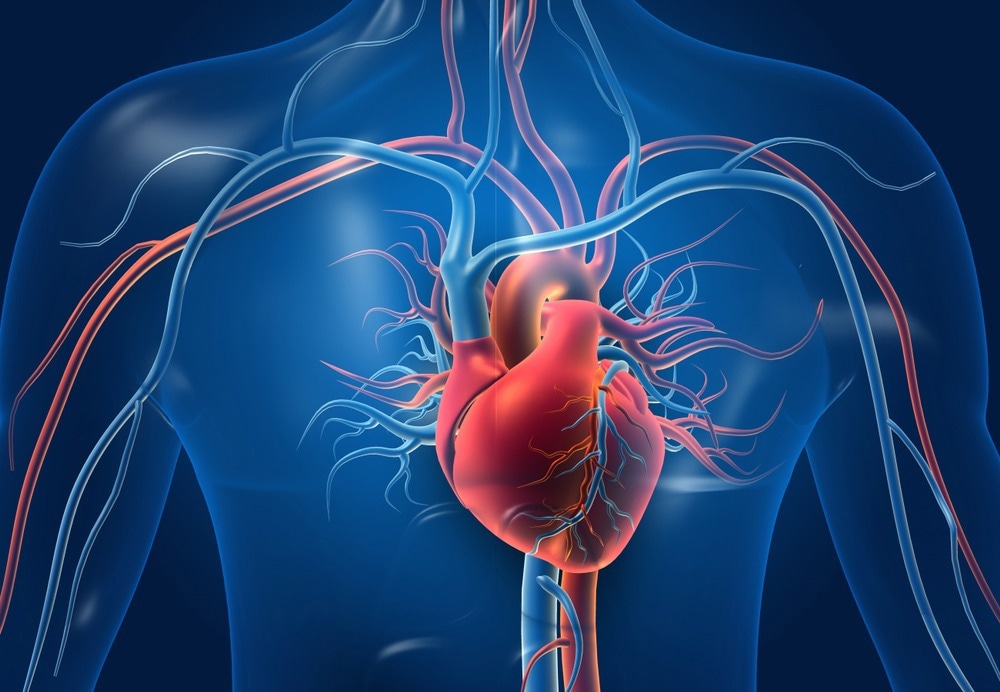

Spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) is a nonatherosclerotic, nontraumatic separation of the coronary arterial walls and causes acute coronary syndrome and sudden cardiac death.

Image Credit: Explode/Shutterstock.com

Coronary arteries are composed of three layers. A dissection occurs when one or more of the inner layers pull away from the outer layer. The torn flap of the arterial woolsacks creates a blockage in blood flow to the heart.

This dissection separation creates a ‘false’ lumen that may exist between the intima and media or between the media and adventitia. The separation observed in this coronary event is due to the development of an intramural hematoma (IMH) in the arterial wall.

This can subsequently compress the arterial lumen and reduce the flow of antegrade (forward direction or movement) blood, i.e., disrupt the flow in the true lumen. This may subsequently result in myocardial ischemia or infarction. Myocardial ischemia occurs when blood flow to the heart muscle (myocardium) is obstructed by a partial or complete blockage of a coronary artery, and an infarction describes the death of tissue (necrosis) due to inadequate blood supply to the affected area.

The epidemiology of SCAD

The overwhelming majority of patients are women, between 87 and 95% of SCAD patients, and are typically between the ages of 44 and 53.

Studies have demonstrated difficulty ascertaining the true prevalence of SCAD; this condition is often underdiagnosed, with variability in its presentations observed. This ranges from mild chest pains to sudden cardiac death. Risk factors for SCAD include:

- Patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome (ACS); SCAD is noted to occur in 3-4% of cases. Among women presenting with ACS, the prevalence is higher, with higher at 8.7% among those <50 years old

- Stable patients presenting for routine coronary angiography; SCAD is noted to occur in 0.3% of cases

- Patients presenting with ST-elevation (finding on an electrocardiogram wherein the trace in the ST segment is abnormally high above the baseline); SCAD is noted to occur in 10.8% of cases

- Women <50 years of age who had a myocardial infarction; SCAD is noted to occur in 24% of cases

- Autoimmune or connective tissue disorders such as Ehler’s Danlos and Marfan-like syndrome

- The result of an organ-specific manifestation of a vascular disorder or arteriopathy. Among these, the most frequent is fibromuscular dysplasia, a noninflammatory, nonatherosclerotic arteriopathy affecting medium-sized arteries.

- In pregnant or early postpartum women, arterial dissection may result from increased physiological hemodynamic stress or hormonal effects that weaken the coronary arterial wall.

Most of these cases were misdiagnosed, highlighting the challenges and underdiagnosis of SCAD.

Pathogenesis and pathophysiology of SCAD

The pathology of SCAD comprises an acute and spontaneous separation of the coronary artery wall layers, forming an intramural space (false lumen). This can sometimes be connected with the true lumen through an intimal tear (flap fenestration).

This subsequently causes a lumen compression, leading to ischemia and acute myocardial infarction. There have been two hypotheses proposed to explain the pathophysiological process:

- The inside-out hypothesis: Blood enters the subintimal space from the true lumen after the development of a flap (an endothelial intimal disruption)

- The outside-in hypothesis: A hematoma develops in the media de novo due to transversing microvessels. In this case, an intramural hematoma forms, which most commonly reabsorbs and heals. Early extension of the intramural hematoma can result in occlusion of the vessel and subsequent development of a tear, resulting in decompression and resumption of flow.

The initiation of this event is proposed to be a hemorrhage at some point in the tunica media or adventitia; however, it remains to be seen whether or not the intimal tear could be the primary event when it is present.

Myocardial ischemia and symptoms associated with this are thought to be the result of either:

- Bulging of the compressed intima by the formation of an intramural hematoma

- Extension of the dissection by forward-moving blood flow causes an obstructive false lumen

- Due to the disturbed hemodynamics and exposed components of the vessel wall to the bloodstream, the incidence of thrombosis

- The arterial dissection and the subsequent healing process could cause chest pain in the absence of myocardial ischemia.

Clinical presentation of SCAD

A high index of suspicion is necessary to prevent misdiagnosis of the condition. Most patients with SCAD present with acute onset chest pain within the increase in cardiac biomarkers. However, between 11 and 16 percent present with cardiogenic shock or ventricular arrhythmias. In terms of electrocardiograms, single-vessel dissection is the most common anatomical presentation.

Managing SCAD

SCAS is typically managed conservatively with an emphasis on prevention. Patients who stop present with acute myocardial infarction with symptoms of ongoing ischemia or hemodynamic compromise are later considered for revascularization or coronary artery bypass grafting. Over the long term, many patients can be managed with long-term aspirin, a combination of antiplatelet therapy (clopidogrel) and aspirin, beta/calcium blockers, and statins.

Revascularisation improves mortality. In those with disease in more than one artery, coronary artery bypass grafts function more successfully than percutaneous coronary interventions.

Most guidelines are centered around preventative strategies, however. A Cochrane review conducted in 2015 found evidence that education and counseling to instigate behavioral change could help mitigate the risk in high-risk groups.

90% of cardiovascular disease is considered preventable if steps are taken to mitigate against risk factors known to be involved in their pathophysiology. Prevention includes regular adequate physical exercise, decreasing body mass index, treating high blood pressure, stopping smoking, and adopting a healthy diet to decrease cholesterol and blood pressure.

Both the use of medication and exercise are considered to be roughly effective. Moreover, the risk of coronary artery disease can be reduced by approximately 1/4 through high levels of physical activity.

References

- Macaya F, Salinas P, Gonzalo N, et al. (2018) Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: contemporary aspects of diagnosis and patient management. Open Heart. doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2018-000884.

- Hayes SN, Tweet MS, Adlam D, et al. (2018) Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.084.

- Yip A, Saw J. (2015) Spontaneous coronary artery dissection-A review. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2223-3652.2015.01.08

Further Reading

- All Coronary Artery Disease Content

- What is Coronary Artery Disease?

- Coronary Artery Disease Pathophysiology

- Coronary Artery Disease Angina

- Coronary Artery Disease Risk Factors

Last Updated: Aug 30, 2023

Written by

Hidaya Aliouche

Hidaya is a science communications enthusiast who has recently graduated and is embarking on a career in the science and medical copywriting. She has a B.Sc. in Biochemistry from The University of Manchester. She is passionate about writing and is particularly interested in microbiology, immunology, and biochemistry.