Neuroscientists aim to understand how the primary motor cortex (M1) can regulate precise movements while supporting behavioral exploration that encounters consistent errors. While consistency in the environment can help animals learn and automate highly reliable actions, they must remain flexible to adapt to environmental changes. In a new report now published in Nature Communications, Sravani Kondapuvulur and a research team in bioengineering, medicine and neurology, at the University of California, San Francisco, U.S., developed a reach-to-grasp task in rats to monitor the neural variability of the primary motor cortex (M1) and dorsolateral striatum (DLS) regions. The results indicated how the motor and striatal areas transitioned between two modes by generating a reliable neural pattern for automatic and precise movements, compared to variable neural patterning observed during behavioral exploration.

How do movement circuits in our brain support both automatic action and flexible movement exploration?

While mobility and motor skills are defined as fast, accurate and consistent actions, they must also be flexible to adjust to a task at hand or to a changing environment. The link between the production of consistent motor skills and behavioral exploration for error correction currently remains elusive. In systems neuroscience, the primary motor cortex is thought of as an engine for precise movement control by generating reliable sequential firing.

In this work, primary author and MD Ph.D. researcher Sravani Kondapuvulur, who is presently completing her doctoral research in the research team of Associate Professor Karunesh Ganguly at UCSF, described the movement circuits in our brain and its impact on mobility. “Every day, most people use learned movements to accomplish daily tasks, such as turning on lights in a room or reaching for and grasping a coffee mug from a cabinet,” she said.

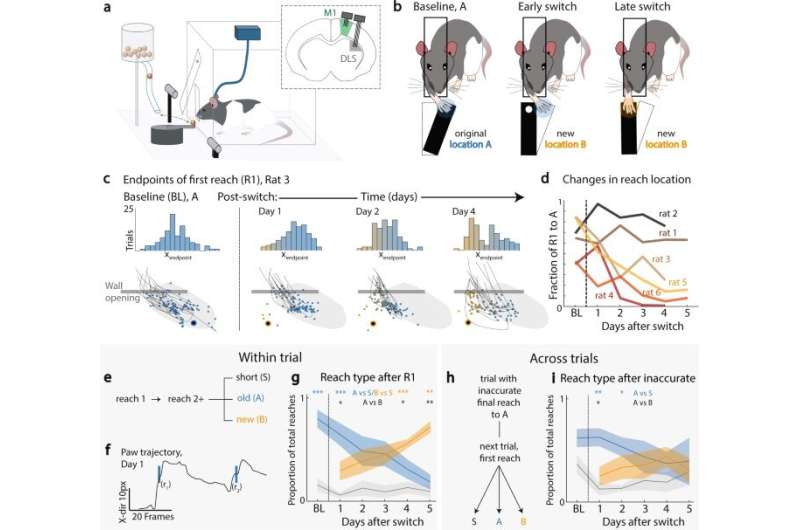

“These movements are often automatic—produced in a fast, accurate, and consistent manner without much overt thought. Yet, a skill should also remain flexible to readily adjust to changes in the environment, such as moving to a different home with alternate light switch and cabinet placement.” Since the process of automatic action and flexible movement are facilitated by circuits in our brain, Kondapuvulur et al sought to examine the underlying mechanisms of the process in an animal model. “We first overtrained rats to reach and grasp for a food reward in a singular location. We then moved the reward to a second, nearby location and observed how they re-learned where to retrieve the pellet,” she said.

Experimental food reward relocation

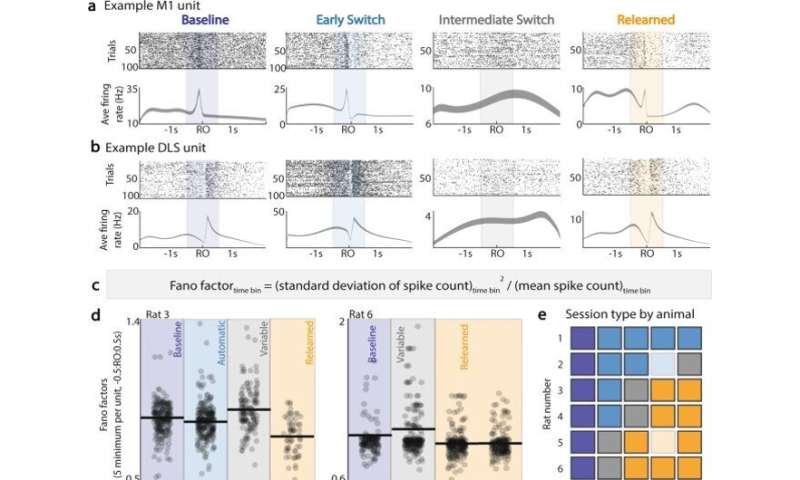

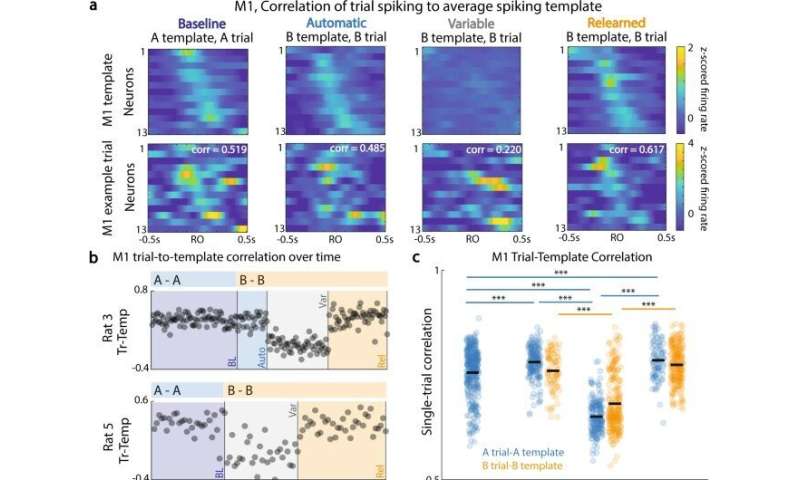

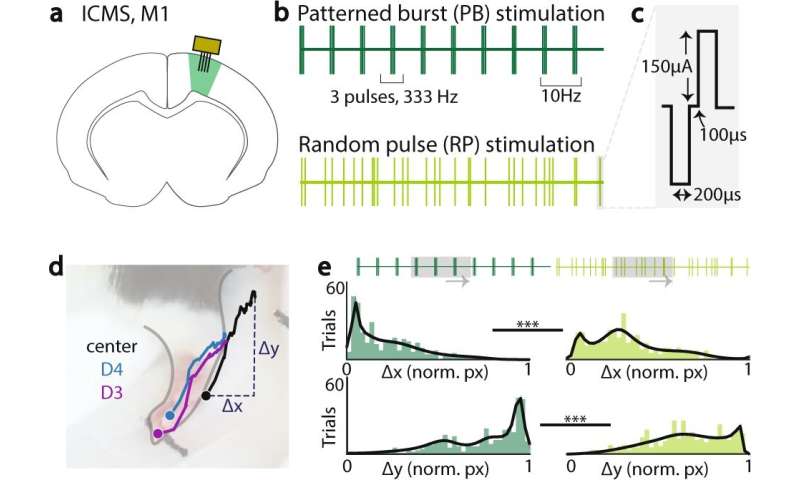

During the experiments, the team were specifically interested in the underlying role of M1 (primary motor cortex) and DLS (dorsolateral striatum) to modify skills, while still largely maintaining the original action. They accomplished this by “recording brain activity from both the primary motor area (M1) and the downstream motor area (DLS).” Kondapuvulur further evaluated their findings: “We found that re-learning was a multi-day process, with many errors of reaching to the old location early on.” She continued, “interestingly, on the day with the greatest breakdown of automatic movement errors,” they noticed “a switch in M1 and DLS brain activity from consistent patterns during the task, to significantly increased variability from trial to trial.”

The team notably observed a close association between the established behavioral exploration; transitioning from the highly predictable ensemble activation in the two neural regions of interest, to a variable state in both regions. Kondapuvulur et al continued the experiments next day to highlight how modifying an automatic skill was a multi-day process.

Re-establishing behavioral flexibility, in time

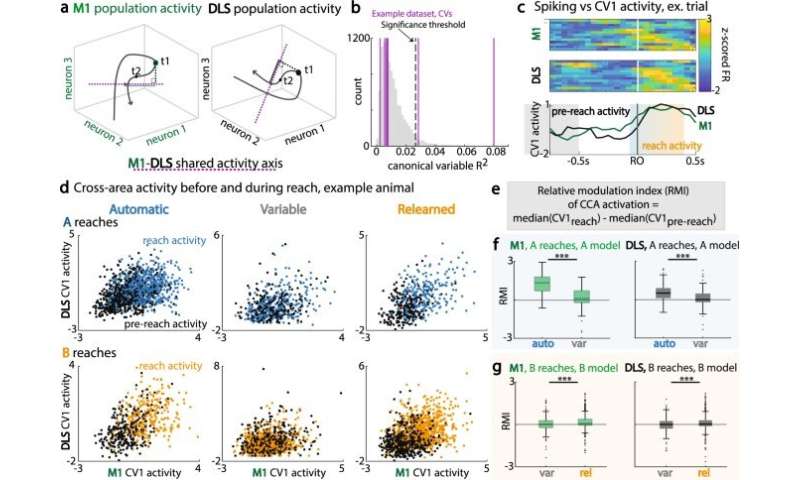

The scientists next sought to understand the neural correlates of re-establishing behavioral flexibility. They observed a loss of the previously stable neural spiking behavior relationship across the two regions, and increased neural variability, which coincided with goal-directed behavioral explorations, and behavioral changes during the switch process. According to Kondapuvulur et al, while examining a potential link between variable neural activity and the process of behavioral exploration, they showed how the “timing of maximal ‘communication’ between the two regions was no longer consistently associated with timing of the reaching behavior.” The outcomes showed that “consistent versus variable timing of electrical activity in the primary motor area could produce correspondingly consistent and variable movements.”

Shared neural activity

In its neural architecture, the primary motor cortex and dorsolateral striatum regions (M1 and DLS) are structurally monosynaptically connected; while DLS also receives inputs from a variety of other cortical and subcortical regions. Kondapuvulur et al therefore explored if, despite the loss of consistent timing to the task, the population spiking remained correlated to each other in the two regions. They accomplished this by examining cross-area communication between the two neural regions and how the areas changed during variable sessions via canonical correlation analysis to represent maximally correlated activity across areas, to identify shared neural activity.

Outlook

The team wrote: “We found that transitioning from automatic, consistent movements to enable flexible exploration involved a transition from consistent to variable motor area activity.” They found the outcome to be significant since “it demonstrates another distinct method of movement learning, separate from novel skill learning, such as playing the piano, when compared to the process of adaptation, i.e., updating fast movements in the face of errors.”

Source: Read Full Article