I was 11 years old when I thought about killing myself for the first time.

Since then, I’ve struggled for more than a decade to overcome suicidal ideations on a regular basis.

These thoughts and feelings can be triggered by some of the most minute things—breaking a mug, being rejected by a potential employer—things that could make anyone feel upset can throw me into a full-blown spiral. It’s one of the many things that I struggle with as someone with bipolar disorder.

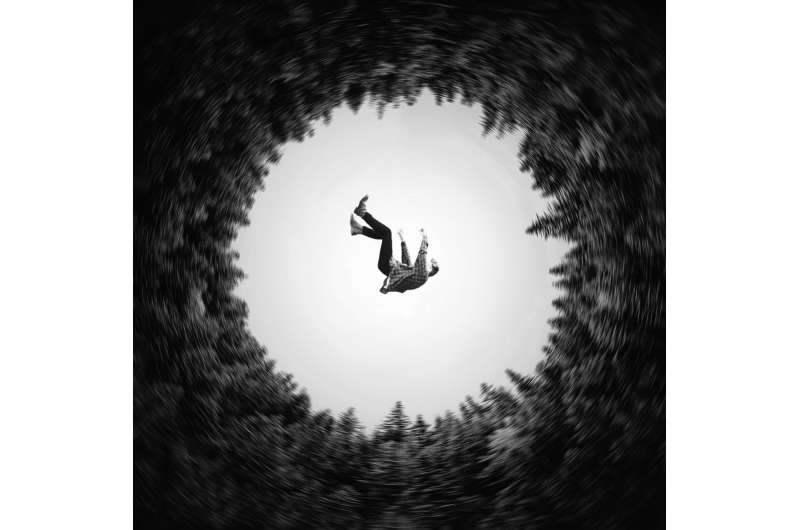

It can feel as if I’m being smothered by a black cloak. Sometimes the feelings can pass as quickly as they came on; sometimes the darkness lingers for longer.

Reporting on mental health issues—like suicide prevention—has been cathartic for me.

In 2020, 45,979 people died by suicide in the U.S., according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It’s now considered to be the nation’s 10th-leading cause of death, and the second-leading cause of death for people 15 to 24, according to the National Institute of Mental Health. Just last year, Surgeon General Vivek H. Murthy issued a public health advisory in response to the rising rates of youth suicides.

But suicides are just the tip of the iceberg, according to Anthony Wood, interim chief executive and chief operating officer of the American Association of Suicidology (AAS), one of the oldest suicide prevention organizations in the U.S. Association data show that 1.2 million people attempted suicide in 2019. The number of those who consider it but don’t act upon those thoughts is immeasurable.

What’s more, data collected from survivors of suicide attempts indicate that almost half of those who do make an attempt considered it for less than 20 minutes. A fourth of them considered it for less than five minutes.

Wood says suicide is associated with a number of causes: Mental illness, life stressors— and just wanting to stop the pain someone is experiencing. The reasons someone dies by suicide are just as unique as they are—which makes prevention and prediction a model, not a science.

Suicide prevention campaigns have been around for decades. Messaging like “know the signs” and “suicide is preventable” are meant to encourage hope with the goal of reducing rates of suicide.

But there is disagreement about their usefulness. Understanding suicide is complicated; so is prevention.

The AAS was one of the first organizations to collect the data from survivors and create what we know as “the signs.” The thought, Wood said, was that if AAS could define warning signs like those for other diseases, physicians and other care professionals could better assess someone’s risk.

But Wood says the association’s signs were never intended to be used on an individual basis outside a clinical setting—by people trying to help friends and loved ones.

According to Dr. Doreen Marshall, vice president of mission engagement with the American Foundation of Suicide Prevention, there’s no one way to predict when or if someone is going to die by suicide. What we do know comes from speaking with those who attempted it and survived and survivors of suicide loss.

Some people become experts in masking their pain, Marshall said, but there are people who give indications they are considering suicide. They’re not quite as specific or clear as prevention messaging suggests, she said, but certain behaviors can be cause for concern.

The three buckets—talk, behavior, mood—Marshall said, are what most experts are using for individual identification of suicidality. Hearing someone say they want to end their lives, seeing them increase substance use, becoming withdrawn—these are some of the more common signs.

If you do recognize some of these behaviors in someone, or are concerned about someone’s mental well-being, there are things you can do to help.

Don’t be afraid to be direct. Some people may believe that bringing up the word “suicide” can be triggering, but if you are concerned that someone is thinking about killing themselves, there’s no time to wait. Ask it outright: “Are you thinking of killing yourself?” Wood said. More often than not, he continued, that person will experience a sense of relief that someone is seeing their pain.

“There’s never any harm in showing that you care about a person,” said Shari Sinwelski, vice president of crisis care at Didi Hirsch, mental health services. And no matter how you ask it, if the answer is “yes,” it’s time to act.

Calling the 988 hotline or other crisis lines is probably the fastest way to reach someone who is trained in suicide intervention. For the long term, helping to set that person up with a long-term mental health care support system is key to saving their lives.

There is a nationwide shortage of mental health professionals, so getting help might take longer than you’d hope for. In that case, you can seek out support groups or other free resources for the person.

People who end their lives are often judged for how they died rather than how they lived, said Ronnie Walker, founder and executive director of Alliance of Hope, a nonprofit that provides support for suicide loss survivors. “Yet, so many were extraordinary people who got to a place where they took action to end their life for whatever reason,” she said.

Like Wood, Walker says survivors can suffer.

Sometimes survivors can experience complicated grief, which is defined by the continued interference of the healing process, like a wound never allowed to heal, according to M. Katherine Shear, Marion E. Kenworthy professor of psychiatry at Columbia School of Social Work and Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons.

Suicide prevention campaigns are important, yet many loss survivors find that they amplify their feelings of guilt, Walker said, especially during suicide prevention month.

Sinwelski says it’s just as important for survivors to build up their support networks.

Reach out to others who have lost someone to suicide. Because of its complexities, the grief process can be best understood by those going through it themselves.

In the end, everyone’s story is unique.

Most people would never guess that I’ve thought about killing myself. I don’t fit “the signs” model. Nor has anyone I’ve lost.

And that’s why it’s so important to continue having these conversations.

Suicide is a fact of life. But in many cases, it can be prevented. And it’s not a matter of knowing the signs, but of changing the way we think about dying by suicide.

Source: Read Full Article