Every day across America, hundreds of children and teens with depression, anxiety, autism and other conditions end up in their local hospital’s emergency department because of a mental or behavioral health crisis.

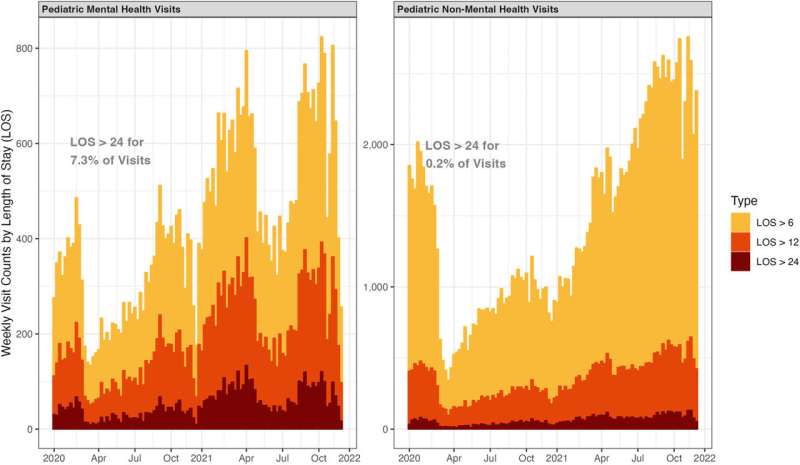

And 12 hours later, 1 in 5 of them will still be in the ED, a study finds.

Another 12 hours after that—a full day after they arrived—1 in 13 of them will still be in the ED. More than 60% of these patients are suicidal or have engaged in self-harm.

Meanwhile, virtually all the children who went to the same hospital for non-mental health emergencies have already received treatment and gone home, or been admitted to the hospital, within 12 hours, the study shows.

Visits of both kinds dropped dramatically in spring 2020, and even a year and a half later, non-mental health emergency visits by kids were still below pre-pandemic levels. But mental health emergency visits climbed steadily. By early 2021 they had exceeded their pre-pandemic levels and stayed there, with seasonal variation.

The study, published in the Journal of the American College of Emergency Physicians Open by a team led by an emergency physician from the University of Michigan and VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System, adds more evidence of the strain faced by the pediatric mental health system. It builds on previously reported data from large teaching hospitals and children’s hospitals.

“Insufficient access to mental health care stands out among the factors that contribute to prolonged stays in the nation’s emergency departments,” said first author Alex Janke, M.D., M.H.S., a National Clinician Scholar at VAAHS and the U-M Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation. “There are too few options outside of emergency care for patients in many communities.”

About 1 in 8 children who go to a community hospital for a mental health emergency end up getting admitted for at least one night or transferred to another hospital, the study finds. That number rose beyond pre-pandemic numbers by early 2021 and has stayed high ever since. Meanwhile, children’s admissions and transfers for other types of emergencies have stayed flat.

Because the hospitals in the study are not part of major academic systems, they likely do not always have child psychiatrists or other specialists in-house to work with emergency medicine teams in assessing and creating treatment plans for children in mental health crisis.

Janke and his colleagues from Yale University, the American College of Emergency Physicians and Columbia University used data from the Clinical Emergency Data Registry, with data from 107 community hospitals from January 2020 to December 2021, plus data from 2019 from 33 of those hospitals.

The majority of emergency department visits by children and teens in the United States happen in such hospitals, Janke notes. More resources that could help families get care in the local community or via telehealth could reduce the need to seek emergency care for their child, he says. Also needed are more resources to support local emergency medicine teams who find themselves caring for a child or teen in mental health crisis.

“While others are studying the epidemiology of mental health concerns among American’s youth at this point in the pandemic, our study focuses on whether the mental health system is ready for what’s coming in the door,” he said. “And the length of emergency department stays that we’re seeing here shows that it is not.”

The data source does not contain information about individual characteristics of the patients seeking care, such as what kinds of mental health care they’ve received, their demographic information, or what caused their families to seek emergency mental health care.

Janke and colleagues are working on further research on this topic. But the study does show that hospitals in the northeastern part of the country were most likely to have longer ED stays than other regions, especially the south and west.

Source: Read Full Article