States of unconsciousness, such as those that occur during sleep or while under the effect of anesthesia, have been the focus of countless past neuroscience studies. While these works have identified some brain regions that are active and inactive when humans are unconscious, the precise contribution of each of these regions to consciousness remains largely unclear.

Researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital recently carried out a study aimed at better understanding the activity of different regions of the cortex, the outer layer of the mammalian brain, during different states of unconsciousness, namely sleep and general anesthesia. Their paper, published in Neuron, identifies distinct cortical networks that are engaged during different states of unconsciousness.

“We have always been interested in trying to understand better how neuronal activity in the brain gives rise to consciousness,” Dr. Rina Zelmann, the lead researcher for the study, told Medical Xpress. “This is a huge and difficult question to answer. In this project, we started with seemingly simple questions, such as: What happens in the human brain when we are unconscious? And, what happens when we cannot be awakened?”

Dr. Zelmann, Dr. Cash, and their colleagues have been recording and investigating activity inside the brain for several years, using brain stimulation techniques. Their recent study on the states of unconsciousness focuses on sleep versus general anesthesia induced by the drug propofol.

“We realized that we were uniquely positioned to study these challenging questions in a constrained way by comparing the response of the human brain to stimulation in different states of consciousness and unconsciousness,” Dr. Zelmann said. “For this project, we assembled an amazing group of neurologists, engineers, electrophysiologists, neurosurgeons, and anesthesiologists.”

The researchers carried out their study on patients diagnosed with epilepsy who had electrodes implanted in their brains as part of their medical treatment. By recording brain activity inside the brain, these electrodes help doctors monitor and treat epileptic seizures. Dr. Zelmann, Dr. Cash, and their colleagues thus asked these patients if they wished to participate in their study.

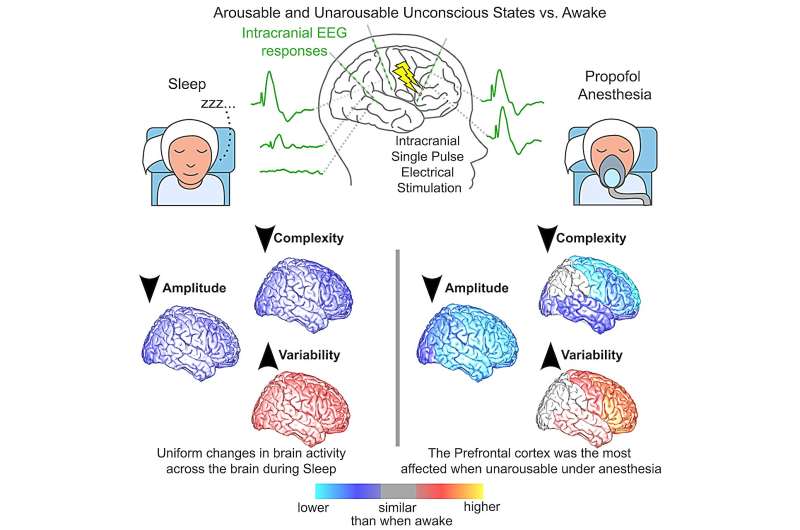

“We used short pulses of electrical stimulation (0.2 ms duration) delivered to different brain regions one by one while recording the brain activity from all the other regions (i.e., where clinical electrodes were),” Dr. Zelmann explained.

“As these patients stay in the hospital for 1–2 weeks while their brain activity is recorded 24/7 with the goal of understanding their seizures, we could do this protocol while they were awake, while asleep, and under general anesthesia right before the electrodes were removed in the operating room. We then compared the responses with different mathematical techniques to understand the difference in the response to stimulation in terms of how complex were the responses, how was the brain network involved, and how consistent were the responses.”

In order to effectively characterize the involvement of different cortical networks during sleep versus under general anesthesia, the researchers compared what happened in the brain of the participants during the unconscious states to what happened when they were awake in the same environment.

Interestingly, Dr. Zelmann and her colleagues found that, compared to when they were awake, during sleep the brain was uniformly affected across patients, presenting simpler and reduced brain connections, as well as larger variability in the recorded activity.

“All measures were more pronounced during propofol-induced anesthesia, but the brain involvement was not uniform; the changes in prefrontal regions were particularly prominent,” Dr. Zelmann said.

“This indicates that during different forms of unconsciousness distinct parts of the brain are involved in different ways. Our findings in turn imply that going from unconscious to conscious may use different mechanisms depending on the nature of the unconscious state.”

Overall, this recent study unveils some of the differences in the activity of cortical networks while humans are unconscious (i.e., during sleep) and when they are in an unconscious state that they cannot be woken from (i.e., while under the effects of propofol-induced general anesthesia).

In the future, these findings could pave the way for new studies further exploring the contribution of the brain regions they identified to unconscious states and our general understanding of consciousness. Meanwhile, Dr. Zelmann and her colleagues plan to continue their research in this area.

“The fact that the human brain responds differently to even a single pulse of stimulation under different states of consciousness also has implications for therapeutic neuromodulation, which is used to help control seizures, and, increasingly, psychiatric problems,” Dr. Zelmann added.

“The stimulation is usually adjusted during waking periods but maybe we should be thinking more about how it changes the brain during sleep too, since they are not the same. We are now planning to continue in this exciting line of research, increasing our understanding of the human brain’s response to stimulation under different states.”

More information:

Rina Zelmann et al, Differential cortical network engagement during states of un/consciousness in humans, Neuron (2023). DOI: 10.1016/j.neuron.2023.08.007

Journal information:

Neuron

Source: Read Full Article