Although immunotherapy has revolutionized the treatment of many blood cancers, the field has encountered challenges developing similar treatments for solid tumors. When it comes to pediatric brain tumors, which are the leading cause of cancer death in children, challenges include both identifying good targets on the surface of the tumors and finding ways to get the treatment into the brain without causing unwanted side effects.

Now, in a new proof-of-concept study published in the Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer, researchers at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) have identified a protein present on the surface of multiple pediatric brain tumors and have found a way to target this protein safely and effectively in the brain using immunotherapy in preclinical models.

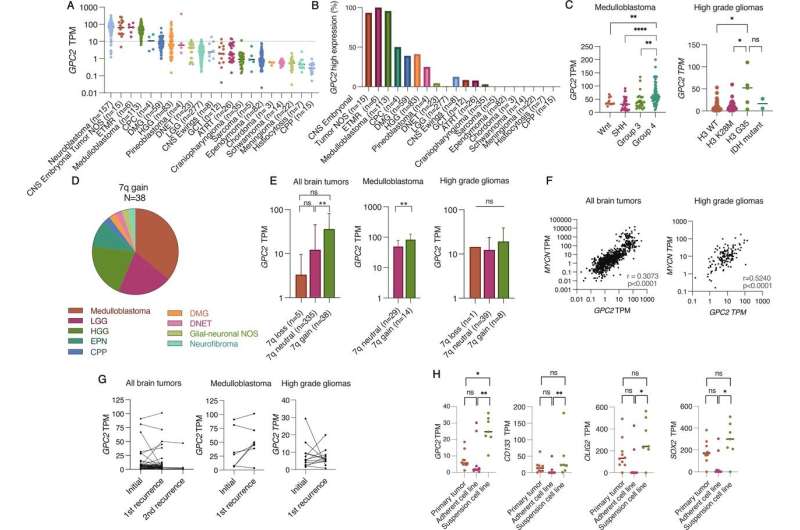

The researchers began by investigating whether glypican 2 (GPC2) is expressed on the surface of brain tumor cells, as prior work at CHOP and elsewhere has shown that the protein is overexpressed on the surface of neuroblastomas and other pediatric and adult tumors. GPC2 has many of the key qualities of a good immunotherapy target, and preclinical work by CHOP researchers and others treating neuroblastoma with GPC2-directed immunotherapy has led to a clinical trial that will begin enrolling in early 2023.

Using RNA sequencing, the researchers found that GPC2 is expressed in several types of brain tumors and is highly expressed in embryonal tumors and medulloblastomas. They found no significant difference in GPC2 expression in tumor tissue taken at the time of diagnosis and at the time of relapse, suggesting GPC2-directed immunotherapy could work in either setting.

The next challenge the researchers undertook was identifying a method for targeting GPC2 in the brain. Immunotherapy for blood cancers relies on a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) that is added to a patient’s T cells using a virus and targets a protein on the surface of cancer cells, turning the T cells into cancer-fighting machines. However, this approach leaves the immunotherapy continuously “turned on”—a suitable approach in the bloodstream, but less desirable in the brain, where CAR-induced swelling and other toxicities could lead to death.

To better control the levels of GPC2-directed CARs in the brain, the researchers used an mRNA delivery system, similar to the approach used for the COVID-19 mRNA vaccines. The researchers purified an mRNA transcript for a CAR targeting GPC2. Using T cells they had collected, the researchers then used a technique known as electroporation to transiently open up the membranes of the T cells and insert the RNA inside. The modified T cells were then tested in in vitro and in vivo models of brain cancer.

The researchers found that their mRNA CARs were effective in attacking medulloblastoma and high-grade glioma tumors in both in vitro and in vivo preclinical models. The CARs were expressed for a shortened timespan—approximately 5-7 days—which, in a clinical setting, would allow for strategic and controlled dosing.

“This work establishes the proof-of-concept efficacy of GPC2-directed CAR T cells in a subset of malignant pediatric brain tumors and the framework to further develop GPC2-directed immunotherapies for children with lethal central nervous system tumors,” said first author Jessica B. Foster, MD, an attending physician in the Division of Oncology at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Source: Read Full Article