Many people have understood that our immune systems get weaker as we age, which in part explains why older people often get less protection than younger ones from annual influenza vaccines.

Now a team of scientists led by experts at Cincinnati Children’s have taken a deeper look at how the immune system changes with age—and what they’ve found could make often-mediocre flu vaccines much more protective.

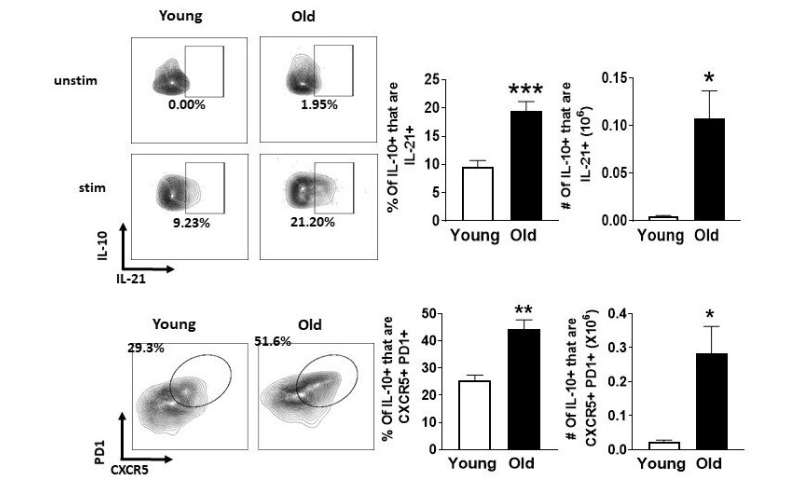

Their study, published online July 29, 2020, in the journal Science Advances, reports that rather than being weaker, the immune system in the elderly is actively suppressed and that this suppression is reversible. Their data show that triggering a strong response to vaccination in the elderly depends on relieving this suppression, which is driven by a key group of cells within our immune system. The co-authors call them “Tfh 10” cells, which stands for Interleukin 10-producing T follicular helper cells.

“These Tfh10 cells accumulate dramatically in our bodies as we age, and they have the effect of making older individuals less responsive to invading pathogens and less responsive to vaccines,” says corresponding author David Hildeman, Ph.D., Interim Director, Division of Immunobiology.

The good news: it appears possible to boost vaccine power by managing Tfh 10 cells in a way that avoids harming the useful roles the cells play in fending off other types of disease.

If successful in the years to come, their approach may increase vaccine efficacy in the elderly, potentially reducing deaths caused by yearly influenza outbreaks, which have claimed 12,000 to 61,000 American lives per year since 2010, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“The age-related variation in response to vaccines is a huge issue,” Hildeman says. “The current influenza vaccine is roughly 90% protective in young people, but only about 30% effective in the elderly.”

Could this discovery apply to future COVID vaccines?

“Yes, it could. As the elderly do not respond well to multiple vaccines, it is highly likely that the elderly will also not respond as well as the young to new vaccines, either for COVID19 or other emerging pathogens,” Hildeman says.

While some might be surprised to see a discovery that could help seniors coming from a pediatric medical center, many lines of research have no real age boundaries.

“Aging starts at birth,” Hildeman says. “Often the lessons we learn about the decline of the immune system in later years can teach us about how the immune system begins in the young. The more we learn about defective immune responses in general, and strategies to overcome them, the more we can help kids with primary immunodeficiencies, and other immunologic diseases.”

A non-stop quest for balance

Scientists at Cincinnati Children’s have been studying the intricate details of the immune system for decades. Since the 1950s and the introduction of the Sabin oral polio vaccine, the medical center has been a leader in vaccine research—including working every year to help update influenza vaccine formulas and most recently recruiting thousands of people to test hopeful vaccines against COVID-19.

The new paper was co-authored by 20 experts at Cincinnati Children’s and the University of Cincinnati plus colleagues in Germany, Alabama, and Indiana. It details a number of forces that act against each other as our immune systems respond over and over to infections. The study also describes how the balance of these elements changes as we age, with certain types of cells building up over the years to become more like harmful clutter instead of useful weapons.

In this study, the co-authors describe Interleukin-6 (IL-6) as a force that contributes to a persistent low-grade state of immune activation called “inflammaging.” This state gets worse with age and appears to make people more likely to become frail, develop Alzheimer’s disease, or suffer the fatal effects of cardiovascular disease.

Meanwhile, the body fights high levels of IL-6 by producing IL-10, known for its anti-inflammatory properties. Over the years, repeated cycles of response and counter-response result in an interleukin arms race that often leaves older bodies with excess levels of both IL-6 and IL-10.

One of the breakthroughs laid out in the new paper was pinpointing exactly where undesirable levels of IL-10 come from. The team conducted dozens of different experiments to chase down false leads and rule out competing ideas, using several of the highest tech methods available today.

“These findings are the result of five years of work stemming from a long-standing collaboration between my lab and Dr. Claire Chougnet’s lab, contributions from several faculty-level scientists, and particularly the hard work of one amazing former graduate student, Dr. Maha Almanan,” Hildeman says.

The detectives ultimately traced excess IL-10 production to the cell type they dubbed Tfh 10. Then, in mouse models, they showed that simple blockade of IL-10 at the time of vaccination could restore the antibody response nearly to the level of young animals.

“Our data suggest that, instead of enhancing proinflammation, transient blockade of IL-10 could be a novel strategy to enhance vaccine responses in the elderly and, due to its transient nature, is unlikely to have untoward effects on autoimmunity, cardiovascular disease, or frailty,” the co-authors state.

What’s next?

While the new paper reflects a combination of advanced computational and experimental lab work, much of which was confirmed in experiments involving mouse models and human cells, more studies are needed to demonstrate that Tfh 10 cells can be safely managed in people. Then more research will be needed to see how much of a boost to vaccine power can be achieved.

“We are currently in the process of testing whether IL-10 blockade will restore vaccine responses in larger mammals,” Hildeman says. “If that proves effective, that would open the door to clinical trials.”

Cincinnati Children’s and the co-authors have filed a patent application for their discovery. Someday, if future projects succeed, the co-authors envision seniors receiving one shot that would temporarily prevent IL-10 from interfering with the body’s response to a vaccine, but not permanently diminish IL-10 levels, and then the vaccine.

Source: Read Full Article