STOCKHOLM, Sweden — The beneficial effects of the duodenal jejunal bypass liner (EndoBarrier, GI Dynamics) may outweigh the risks for some patients with type 2 diabetes, new data suggest.

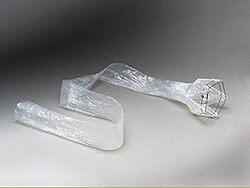

The EndoBarrier, a 60-cm implantable sleeve, is endoscopically placed into the first part of the small intestine, creating a physical barrier between receptors in the intestinal wall and food. The mechanism mimics that of the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass bariatric procedure. It is placed for 12 months and then removed. It has been shown to lead to weight loss and improve A1c levels in people with type 2 diabetes and obesity.

The device has never been approved in the United States. It had received a CE Mark in 2010 for the treatment of type 2 diabetes and obesity, but that was revoked in 2017 after the US Food and Drug Administration halted a pivotal US trial because of a 3.5% hepatic abscess rate. At the time, more than 3000 patients had received the implant.

Now, GI Dynamics has applied for restoration of the CE Mark and launched a new pivotal clinical trial in the United States.

Registry data for more than 1000 patients in several countries implanted with EndoBarrier when it was available showed a much lower hepatic abscess rate of just 1.1%.

The real-world data were presented September 20 here at the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) 2022 Annual Meeting by Bob Ryder, MD, clinical lead of the Association of British Clinical Diabetologists (ABCD) audits of new diabetes therapies and devices.

Likely Benefits of EndoBarrier Outweigh the Risks

EndoBarrier, a duodenal jejunal bypass liner

“The international data from the EndoBarrier worldwide registry suggest that the likely benefit of EndoBarrier treatment outweigh the risks,” said Ryder, who has conducted two clinical trials of the EndoBarrier within the UK National Health Service that are due to be published soon.

He told Medscape Medical News that the device isn’t first-line therapy for type 2 diabetes or obesity but may be an alternative to bariatric surgery when lifestyle and pharmacotherapy aren’t effective.

“You wouldn’t use it until you’ve tried everything else. [Compared with bariatric surgery], this is easy. You just slip the EndoBarrier in, [patients] lose a stack of weight, and their diabetes gets better.”

Asked for comment, session moderator Leszek Czupryniak, MD, PhD, told Medscape Medical News: “It’s an interesting device that has been around for quite some time already. This was a vast group with very impressive results. The most interesting thing was that you have [the EndoBarrier] implanted for a year and then it changes your life so much. You lose weight, it probably changes your lifestyle, and then you’re able to maintain this lost body weight for years.”

Regarding the target patient population, Czupryniak said: “I would say patients in whom pharmacotherapy failed, or they can’t afford to pay for [glucagon-like peptide-1 agonists] long-term. Also, patients who won’t agree to be operated on.”

“For those with a [body mass index (BMI)] of 50 kg/m2 or more who are no longer able to move around easily, there’s very little to offer, whether they have diabetes or not. This is something between pharmacotherapy and surgery, or perhaps could be combined with pharmacotherapy. And it’s reversible, so if they don’t like it you can take it out,” added Czupryniak, who is head of the diabetes and internal medicine department at the University of Warsaw, Poland.

A1c, Weight, Cholesterol, and Blood Pressure Improved

The independent, secure, online registry was established under the auspices of ABCD in 2017 for the collection of EndoBarrier data worldwide after it had been withdrawn from multiple markets where it had been approved. As of March 2022, data had been submitted for 1022 patients from 34 centers in 10 countries, including Australia, Austria, Brazil, Czech Republic, England, Germany, Israel, Netherlands, Scotland, and Slovenia.

Patients were a mean age of 51.3 years, 52.5% were men, average BMI was 41.1 kg/m2, and 84.9% had type 2 diabetes.

The device is inserted endoscopically during a 40-minute outpatient procedure and is intended to stay in place for just a year. It aids weight loss by preventing food absorption along a section of the duodenum and jejunum and is cheaper than bariatric surgery, at around $3000, compared with $10,000 for a procedure such as gastric bypass.

From baseline to time of EndoBarrier explant, patients lost a mean 13.3 kg (29 lb), dropping from an average weight of 120 kg to 106.9 kg. A1c decreased by 13.7 mmol/mol (from 67.6 to 53.9 mmol/mol) or 1.3 percentage points (from 8.3% to 7.1%), systolic blood pressure by 6.3 mmHg (from 135.6 to 129.5 mmHg), and cholesterol by 0.6 mmol/L (from 4.8 to 4.2 mmol/L) (all P < .001).

A1c reductions varied significantly by baseline level, ranging from a drop of 17.0 mmol/L for those with baseline levels ≥ 53 mmol/L (7%) to a drop of 34.9 mmol/mol for those with baseline levels ≥ 86 mmol/mol (10%) (all P < .001).

Ryder also presented individual case reports of patients who, in addition to experiencing significant weight loss and A1c reductions, also had improvements in fatty liver, obstructive sleep apnea, and renal function.

“It‘s Not a Dangerous Device”

Serious adverse events occurred in 43 patients or 4.2% of the overall cohort. These included early removal because of gastrointestinal bleeding in 2.3% (24 patients), liver abscesses in 1.1% (11 patients, including eight prompting early removal and three found at time of routine explant), early removal because of pancreatitis or cholecystitis in 0.4% (4 patients), and liver abscess after prolonged implant of more than 1 year in 0.2% (2 patients).

One patient had early removal because of liner obstruction, and another had an abdominal abscess due to a small bowel perforation related to the EndoBarrier.

Less serious adverse events occurred in 13.6% of patients (139 patients). These included early removal because of gastrointestinal symptoms or migration or liner obstruction in 7.3% (75 patients) and precautionary hospitalization for gastrointestinal symptoms, difficult removal, or endoscopy in 6.3% (64 patients).

“All patients with a serious adverse event made a full recovery and most experienced considerable benefit from the treatment despite the adverse event,” Ryder said.

Czupryniak commented, “It’s a bold decision to put something like this in the body. It also shows how desperate people with obesity are to lose weight.”

However, Czupryniak also noted, “the 1.0% is still low. If you do any mechanically invasive procedure, it would be weird if nothing happened in a thousand patients. The rate is a little bit higher than complications in bariatric surgery. You’d expect 1% to 2% perioperative complications. It’s not a dangerous device. You just have to be wary that something might happen.”

Does It Work Long-Term?

In response to an audience question about long-term results after explant, Ryder acknowledged that about 25% of participants regained weight over time.

But, he said, most did not, suggesting patients were motivated by the weight loss induced by the device. “I think the EndoBarrier facilitated considerable weight loss. [Patients] felt so great about having this happen to them…that they basically broke the vicious cycle that kept them in this state, and a lot of them were able to just maintain the improvement because they didn’t want to go back because they hated where they’d been.”

Czupryniak commented: “This is really interesting. When you stop medication for weight loss, about 90% of people regain the weight. Only bariatric surgery offers similar or even greater level of maintenance. The 25% here is pretty high in general, but we would expect if you stop any weight loss intervention almost anybody will regain weight. Here it’s only 25%.”

Ryder has reported receiving speaker fees, consultancy fees, and/or educational sponsorships from Abbott, BioQuest, GI Dynamics, and Novo Nordisk. Czupryniak has reported receiving consultancy and/or speaker fees from Sanofi, Boehringer Ingelheim, MSD, Lilly, Novo Nordisk, AstraZeneca, Roche, and Abbott.

EASD 2022. Presented September 20, 2022. Abstract OP 09.

Miriam E. Tucker is a freelance journalist based in the Washington, DC, area. She is a regular contributor to Medscape, with other work appearing in The Washington Post, NPR’s Shots blog, and Diabetes Forecast magazine. She is on Twitter: @MiriamETucker.

For more diabetes and endocrinology news, follow us on Twitter and Facebook.

Source: Read Full Article