Breast cancer is harmful enough on its own, but when cancer cells start to metastasize—or spread into the body from their original location—the disease becomes even more fatal and difficult to treat.

Thanks to new research published in Oncogene from the lab of University of Colorado Cancer Center associate director of basic research Heide Ford, Ph.D., in collaboration with Michael Lewis, Ph.D., from Baylor College of Medicine, doctors may soon have a better understanding of one mechanism by which metastasis happens, and of potential ways to slow it down.

“Metastasis is a huge problem nobody’s tackled very well,” says Ford, who holds the Grohne Endowed Chair in Cancer Research at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. “People don’t know how to inhibit the process of metastasis, nor how to inhibit the growth of metastatic cells at secondary sites. And that’s what kills most cancer patients. A lot of common drugs, whether they’re targeted drugs or chemotherapies that are less targeted, do pretty well at inhibiting the primary tumor, but by the time cells metastasize, they’ve changed enough that they don’t get inhibited by those drugs.”

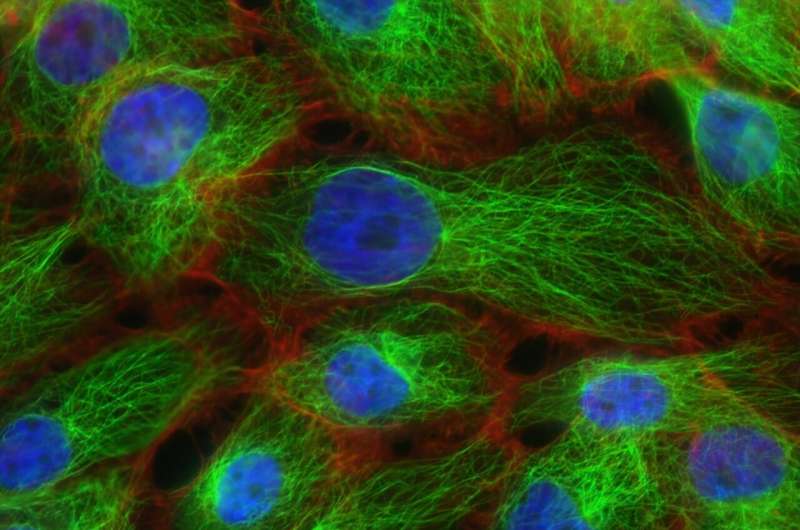

The transformation Ford and her team are studying happens when cells called epithelial cells, which are more adherent to one another and less likely to spread to other parts of the body, start to take on the characteristics of mesenchymal cells, which are more migratory and more likely to invade other parts of the body. This transformation is referred to as the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition.

“When the epithelial cancer cells take on these characteristics of mesenchymal cells, they become less attached to their neighbor and they become more able to degrade membranes, so they can get into the bloodstream more easily,” Ford says.

In 2017, Ford published a paper showing that the metastasis process is helped along when cells that have undergone the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition start “talking” to cells that haven’t, making those cells more likely to gain metastatic properties.

In a new paper published in December, Ford and her researchers, in a collaborative study done with Lewis and colleagues at Baylor College of Medicine, posit that the crosstalk is facilitated by a naturally occurring protein called VEGF-C.

“VEGF-C is secreted by the cells. It binds to receptors on these neighboring cells and then activates a pathway called the hedgehog signaling pathway, though it bypasses the traditional way of activating this pathway,” Ford says. “That turns on a signaling mechanism that ultimately results in activation of a protein called GLI that makes these cells more invasive and more migratory.”

In their new paper, Ford, Lewis and their researchers show that if you can inhibit production of VEGF-C, you can significantly slow metastasis.

“If you take out the receptor that receives the signal from the cells that have not undergone a transition, or if you take VEGF-C out of the mix, you can’t stimulate metastasis to the same degree,” she says. “If you remove that ability for these different cell types to crosstalk, now these cells that never underwent a transition can’t move as well anymore. They can’t metastasize as efficiently.”

The researchers are now in the early stages of animal trials to find out the best way to target that signaling pathway in order to better inhibit metastasis. They want to find out if they can stop metastasis from happening at all, and if they can slow its progression in patients in whom the metastatic process has already begun—and to see if they can inhibit tumor growth at the secondary site.

Source: Read Full Article