So few people came for COVID-19 vaccinations in one county in North Carolina that hospitals there now allow anyone 16 or older to get a shot, regardless of where they live. Get a shot, get a free doughnut, the governor said.

Alabama, with the country’s lowest vaccination rate, launched a campaign to convince people the shots are safe. Doctors and pastors joined the effort.

On the national level, the Biden administration this week launched a “We Can Do This” campaign to encourage holdouts to get vaccinated against the virus that has claimed over 550,000 lives in the U.S.

The race is on to vaccinate as many people as possible, but a significant number of Americans are so far reluctant to get the shots, even in places where they are plentiful. Twenty-five percent of Americans say they probably or definitely will not get vaccinated, according to a new poll from The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research.

They are leery about possible side effects. They tend to be Republican, and they are usually younger and less susceptible to becoming critically ill or dying if they catch COVID-19.

There’s been a slight shift, though, since the first weeks of the nation’s largest-ever vaccination campaign, which began in mid-December. An AP-NORC poll conducted in late January showed that 67% of adult Americans were willing to get vaccinated or had already received at least one shot. Now that figure has climbed to 75%.

That, experts say, moves the nation closer to herd immunity, which occurs when enough people have immunity, either from vaccination or past infection, to stop uncontrolled spread of a disease.

Anywhere from 75% to 85% of the total population—including children, who are not currently getting the shots—should be vaccinated to reach herd immunity, said Ali Mokdad, professor of health metrics sciences at the University of Washington School of Public Health.

A little over three months after the first doses were given, nearly 100 million Americans, or about 30% of the population, have received at least one dose.

Andrea Richmond, a 26-year-old freelance web coder in Atlanta, is among those whose reluctance is easing. A few weeks ago, Richmond was leaning toward not getting the shot. Possible long-term effects worried her. She knew that an H1N1 vaccine used years ago in Europe increased risk of narcolepsy.

Then her sister got vaccinated with no ill effects. Richmond’s friends’ opinions also changed.

“They went from, ‘I’m not trusting this’ to ‘I’m all vaxxed up, let’s go out!'”

Her mother, a cancer survivor, whom Richmond lives with, is so keen for her daughter to get vaccinated that she signed her up online for a jab.

“I’ll probably end up taking it,” Richmond said. “I guess it’s my civic duty.”

But some remain steadfastly opposed.

“I think I only had the flu once,” said Lori Mansour, 67, who lives near Rockford, Illinois. “So I think I’ll take my chances.”

In the latest poll, Republicans remained more likely than Democrats to say they will probably or definitely not get vaccinated, 36% compared with 12%. But somewhat fewer Republicans today are reluctant. Back in January, 44% said they would shy away from a vaccine.

For some, suspicion lingers: of the vaccine, of the government, or both.

“I have lost my trust in the organs of government that are in charge of this thing,” said Richard Matic, 53, of Boca Raton, Florida. “There’s just been so much to cast doubt that they have the best interest of the public in mind, starting with the election, which I believe was stolen.”

Matic does not doubt the coronavirus is real—he became sick with it twice and endured vomiting, diarrhea, headaches and strange, repetitive dreams of geometric shapes. But he said he would wait at least a year before taking the vaccine, giving time to see if negative side effects occur and to judge its effectiveness.

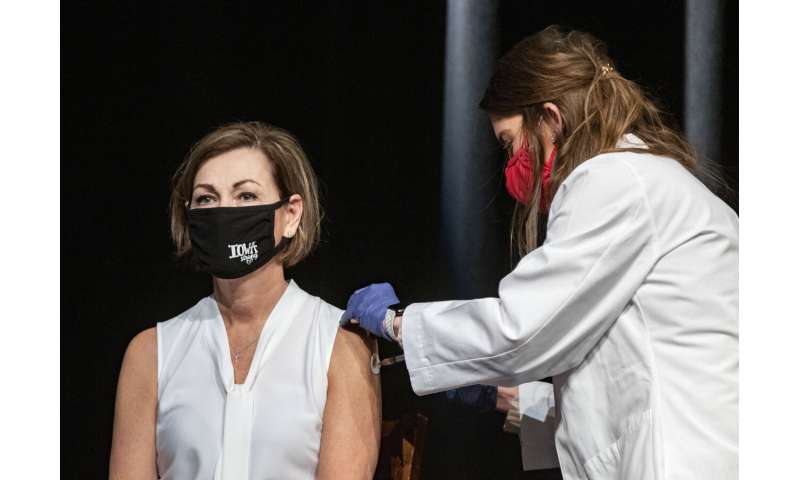

Iowa Gov. Kim Reynolds, a Republican, is trying win over the one-third of adult Iowans who will not commit to getting a vaccine by emphasizing that the shots will help return life to normal.

The Biden administration’s campaign features TV and social media ads. Celebrities and community and religious figures are joining the effort.

In Alabama, health officials targeted a few counties with their pro-vaccine message, enlisting doctors and pastors and using virtual meetings and the radio to spread the word. Dr. Karen Landers, assistant state health officer, said the effort had positive results and was likely to expand.

Nearly 36% of North Carolina adults have been at least partially vaccinated, state data show. But demand has been much lower in certain parts of the state. In Cumberland County, fewer than 1 in 6 residents have gotten at least one shot.

Amid worries there would be an unused surplus of vaccines, Cape Fear Valley Health hospital systems opened up the shots last week to everyone 16 or older.

“Rather than have doses go unused, we want to give more people the chance to get their vaccine,” said Chris Tart, a Cape Fear Valley Health vice president. “We hope this will encourage more people to roll up their sleeve.”

On Wednesday, Gov. Roy Cooper, a Democrat, tweeted a video of him getting a free doughnut from the Krispy Kreme chain. Customers who show their vaccine card can get a free doughnut every day for the rest of the year.

“Do it today, guys!” Cooper encouraged viewers.

Younger people are more likely to forgo a shot. Of those under 45, 31% say they will probably or definitely forgo a shot. Only 12% of those aged 60 and older say they will not get vaccinated.

Ronni Peck, a 40-year-old mother of three from Los Angeles, is one of those who plans to avoid getting vaccinated, at least for now. She’s concerned that vaccines have not been studied for long-term health effects. She senses that some friends disapprove of her stance.

“But I’ve stopped caring about whether or not I feel ostracized and instead have learned to spend more time caring about if I’m doing the right thing for myself and my kids,” Peck said.

Deborah Fuller, a professor with the University of Washington School of Medicine, said if the herd immunity level cannot be reached soon, a more realistic target could be vaccinating at least 50% of the population by this summer, with a higher vaccination rate among the most vulnerable to reduce severe disease, hospitalizations and deaths.

Source: Read Full Article