When fighting disease, our immune cells need to reach their target quickly. Researchers at the Institute of Science and Technology Austria (ISTA) have now discovered that immune cells actively generate their own guidance system to navigate through complex environments. This challenges earlier notions about these movements.

The researchers’ findings, published in the journal Science Immunology, enhance our knowledge of the immune system and offer potential new approaches to improve human immune response.

Immunologic threats like germs or toxins can arise everywhere inside the human body. Luckily, the immune system—our very own protective shield—has its intricate ways of coping with these threats. For example, a crucial aspect of our immune response involves the coordinated collective movement of immune cells during infection and inflammation. But how do our immune cells know which way to go?

A group of scientists from the Sixt group and the Hannezo group at the Institute of Science and Technology Austria (ISTA) addressed this question. In their study the researchers shed light on the immune cells’ ability to collectively migrate through complex environments.

Dendritic cells—the messengers

Dendritic cells (DCs) are one of the key players in our immune response. They function as a messenger between the innate response—the body’s first reaction to an invader, and the adaptive response—a delayed reaction that targets very specific germs and creates memories to fight off future infections. Like detectives, DCs scan tissues for intruders.

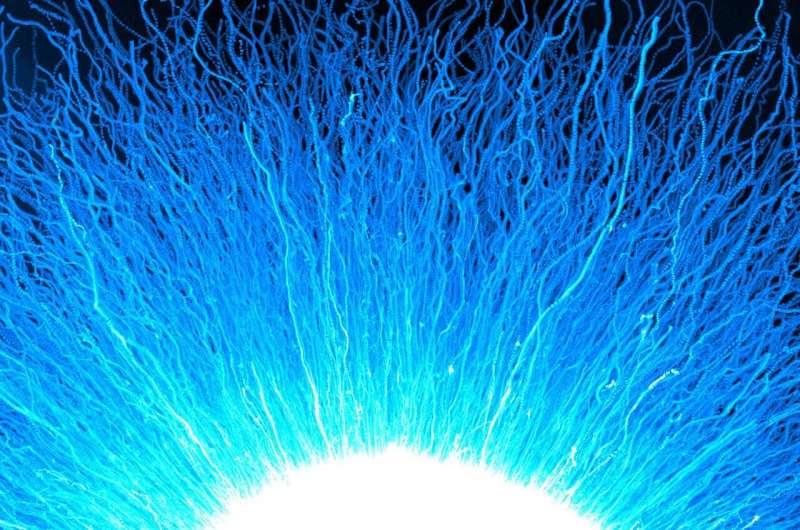

Once they locate an infection site, they are activated and immediately migrate to the lymph nodes, where they hand over the battle plan and initiate the next steps in the cascade. Their migration towards the lymph nodes is guided by chemokines—small signaling proteins released from lymph nodes—that establish a gradient.

In the past, it was believed that DCs and other immune cells react to this external gradient, moving along towards a higher concentration. However, novel research conducted at ISTA now challenges this notion.

One receptor—two functions

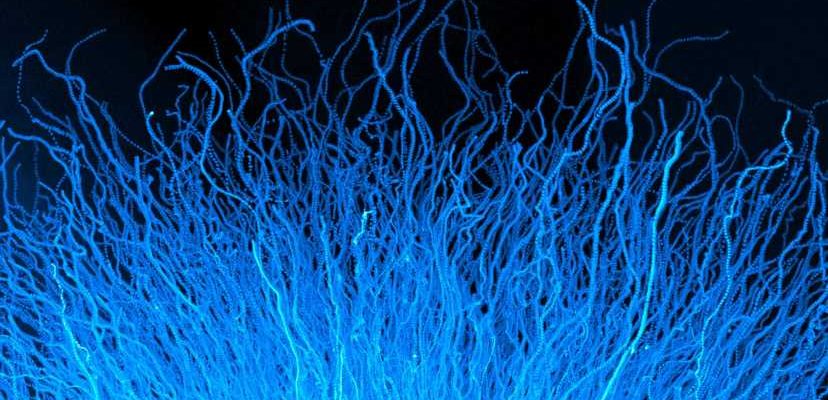

The scientists took a close look at a receptor—a surface structure found on activated DCs called “CCR7.” CCR7’s essential function is to bind to a lymph node-specific molecule (CCL19), which triggers the next steps of the immune response. “We found that CCR7 not only senses CCL19 but also actively contributes to shaping the distribution of chemokine concentrations,” Jonna Alanko, a former postdoc from the lab of Michael Sixt, explains.

Using different experimental techniques, they demonstrated that as DCs migrate, they take up and internalize chemokines via the CCR7 receptor, resulting in local depletion of chemokine concentration. With less signaling molecules around, they move further into higher chemokine concentrations. This dual function allows immune cells to generate their own guidance cues to orchestrate their collective migration more effectively.

Movement depends on cell population

To understand this mechanism quantitatively at the multicellular scale, Alanko and colleagues teamed up with theoretical physicists Edouard Hannezo and Mehmet Can Ucar, also at ISTA. With their expertise in cell movement and dynamics, they established computer simulations that were able to reproduce Alanko’s experiments.

With these simulations, the scientists predicted that the dendritic cells’ movement not only depends on their individual responses to the chemokine but also on the density of the cell population. “This was a simple but nontrivial prediction; the more cells there are the sharper the gradient they generate—it really highlights the collective nature of this phenomenon,” says Can Ucar.

Additionally, the researchers found that T cells—specific immune cells that destroy harmful germs—also benefit from this dynamic interplay to enhance their own directional movement. “We are eager to find out more about this novel interaction principle between cell populations with ongoing projects,” the physicist continues.

Enhancing the immune response

The discoveries are a step in a new direction for how cells move inside our bodies. In contradiction to what was previously believed, immune cells not only respond to chemokines, but they also play an active role in shaping their own environment by consuming these chemical signals. This dynamic regulation of signaling cues provides an elegant strategy to guide their own movement and that of other immune cells.

This research has significant implications for our understanding of how immune responses are coordinated within the body. By uncovering these mechanisms, scientists could potentially design new strategies to enhance immune cell recruitment to specific sites, such as tumor cells or areas of infection.

More information:

Jonna Alanko et al, CCR7 acts as both a sensor and a sink for CCL19 to coordinate collective leukocyte migration, Science Immunology (2023). DOI: 10.1126/sciimmunol.adc9584. www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciimmunol.adc9584

Journal information:

Science Immunology

Source: Read Full Article