Invoking a sense of guilt—a common tool used by advertisers, fundraisers and overbearing parents everywhere—can backfire if it explicitly holds a person responsible for another’s suffering, a meta-analysis of studies revealed.

While guilt is widely used to try and persuade people to act, research has been mixed on its effectiveness in spurring behavior change. This analysis, published in the journal Frontiers in Psychology, found that overall guilt had only a small persuasive effect, which is in line with previous research.

However, researchers uncovered that guilt worked better when it was more “existential,” meaning it appealed to a person’s general desire to better society rather than giving them direct responsibility for a specific problem, a tactic that might be seen as overly manipulative.

“Guilt can be effective, but it will not generate some magic outcome,” said lead author Wei Peng, an assistant professor in Washington State University’s Murrow College of Communication. “The surprising finding from this meta-analysis is that making people feel they are responsible for misdeeds or transgressions is not actually effective. Practitioners may want to consider the many different factors that make guilt appeals more persuasive.”

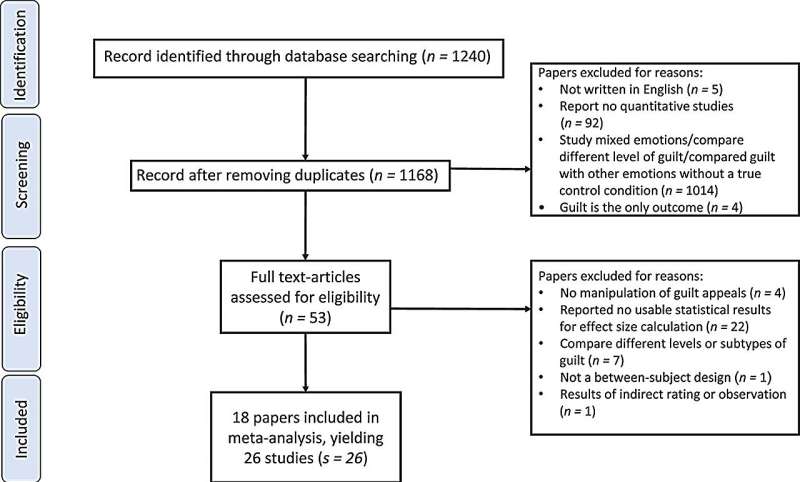

For this study, researchers analyzed data from 26 studies involving more than 7,500 participants. In addition to the effect of responsibility, they found that guilt seems to work better when it is clear that the problem can be changed and possible actions to take are proposed.

Peng and his colleagues also found that guilt was more persuasive with certain subject matter: namely in environmental and educational issues. It was less effective in health communications. The authors noted that health topics may be complicated by the fact that the desired behavior can affect the individual as well as hold benefits for others, such as getting vaccinated for COVID-19.

This analysis also showed that guilt can be an effective motivator for action when it comes to distant and broader issues, such as people suffering after a natural disaster or from social injustice.

Guilt, like pride and shame, is thought to be a unique emotion to human beings, tied to high-level pursuits that go beyond meeting an individual’s basic needs, Peng said, such as a person’s role in creating a better group, country or overall human society. This may help explain why inducing guilty feelings in relation to more distant issues work better than ones that are very personal.

“When people want to use guilt in an appeal, it may be better to use it implicitly to try to make other people feel they should take on this responsibility, rather than say explicitly that they are responsible for what other people are suffering,” Peng said.

More information:

Wei Peng et al, When guilt works: a comprehensive meta-analysis of guilt appeals, Frontiers in Psychology (2023). DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1201631

Journal information:

Frontiers in Psychology

Source: Read Full Article