A team of psychiatrists and bioengineers at Stanford University has found that artificially speeding up a mouse’s heart rate leads to increases in symptoms of anxiety. In their study, published in the journal Nature, the group found a way to speed up the heart rate of lab mice without impacting other parts of its body and used that method to learn more about what happens in the brain when the heart speeds up. Yoni Couderc and Anna Beyeler with Bordeaux University, have published a News and Views piece in the same journal issue outlining the work done by the team in California.

Prior research and anecdotal evidence have shown that in conditions of fear or anxiety, the heart responds by beating faster. For many years, medical scientists have wondered if the reverse is true—is it possible that something other than the brain speeding up the heart rate could lead to an increase in fear or anxiety? To find out, the researchers had to find a way to speed up the heart without impacting other parts of the body.

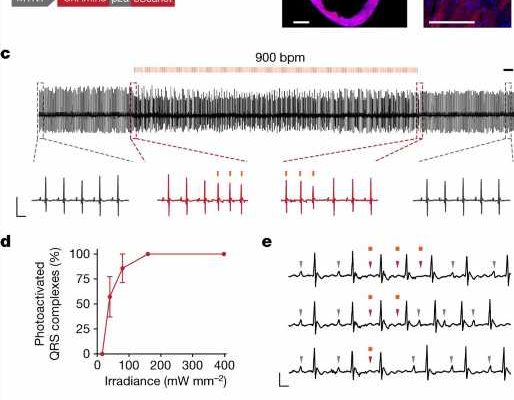

Speeding up the heart rate artificially is easy; there are many drugs, such as caffeine, that influence heart rate. But they also impact other parts of the body, such as the brain. To find out what happens when the heart speeds up absent any other side effects, the researchers looked to a protein made by algae, called ChRmine. When exposed to light, a reaction occurs that allows charged particles to pass through—without the light, such particles are blocked.

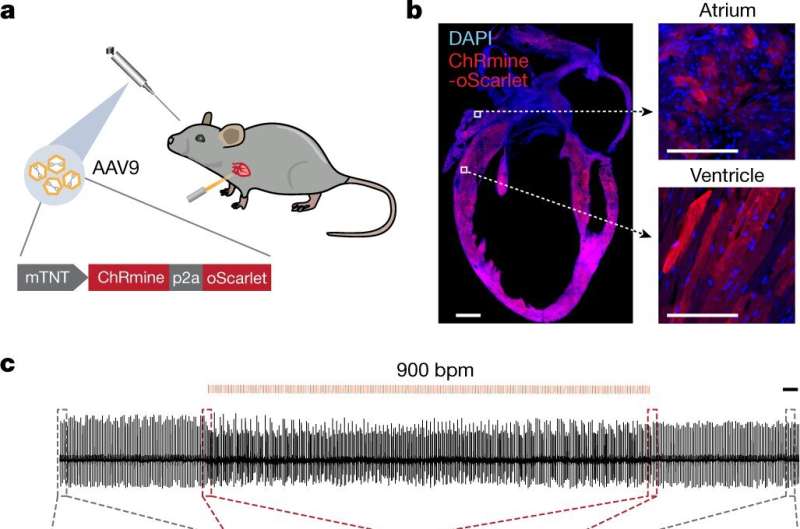

The team applied ChRmine to the outside layer of hearts in living mice and then closed up their chests. They then placed vests with lights sewn in them on the mice. Turning on the lights opened the gates, allowing already present charged particles to move into the heart, resulting in an increase in heart rate.

The researchers then placed the mice in a test stress box and found that speeding up their heart rates induced the mice to behave as they normally do when anxious or scared. Further testing showed that when their heart rates were artificially sped up, parts of their insular cortex lit up, a physical sign of anxiety. Blocking such activity allowed the mice to relax when subjected once again to the box stress test.

More information:

Brian Hsueh et al, Cardiogenic control of affective behavioural state, Nature (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-023-05748-8

Yoni Couderc et al, How an anxious heart talks to the brain, Nature (2023). DOI: 10.1038/d41586-023-00502-6

Journal information:

Nature

Source: Read Full Article