The 160-bed hospital in the Po River Valley town of Chiari has no more room for patients stricken with the highly contagious variant of COVID-19 first identified in Britain that has put hospitals in Italy’s northern Brescia province on high alert.

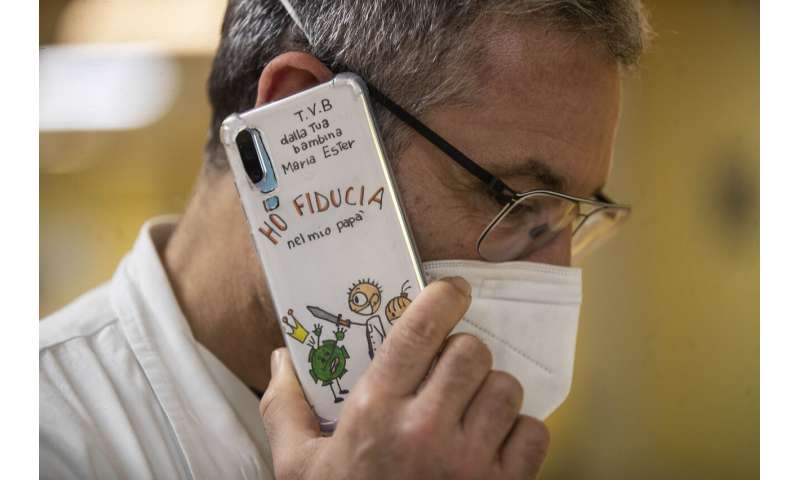

That history was repeating itself one year after Lombardy became the epicenter of Italy’s pandemic was a sickening realization for Dr. Gabriele Zanolini, who runs the COVID-19 ward in the M. Mellini Hospital in the once-walled city that maintains its medieval circular street pattern.

“You know that there are patients in the emergency room, and you don’t know where to put them,” Zanolini told The Associated Press.

“This for me is anguish, not to be able to respond to people who need to be treated. The most difficult moment is to find ourselves again in a state of emergency, after so much time.”

The U.K. variant surge has filled 90% of hospital beds in Brescia province, bordering both Veneto and Emilia-Romagna regions, as Italy crossed the grim threshold of 100,000 pandemic dead on Monday and marks the one-year anniversary Wednesday of Italy’s draconian lockdown, the first in the West.

While Zanolini was able to offer a safety valve to hard-hit Bergamo during last spring’s deadly surge, and to Milan and Varese in the fall, now he must ask hospitals elsewhere in the region to take virus patients he himself cannot admit.

New measures are again being considered in Rome to tamp down the increase in new cases attributed to virus variants, including also those identified in South Africa and Brazil. With the U.K. variant prevalent in Italy and racing from school age children and adolescents through families, Lombardy has again put all schools on distance learning, as have several regions in the south where the health care system is more fragile.

In this surge, patients in the Chiari hospital COVID-19 ward are increasingly family members—husbands and wives, fathers and sons—Zanolini said. And unlike previous spikes, the average age has dropped, with many of the virus patients needing breathing aid between 45 and 55 years of age. “We have seen, however, that they respond well to treatment,” Zanolini said of the younger patients, noting that mortality remains high among the elderly.

Despite months of renewed restrictions starting in October, Italy’s death toll remains stubbornly high—several hundred a day. It topped 100,000 this week, the second-highest in Europe after Britain.

Italy’s new premier, Mario Draghi, is focusing on vaccines to help the country emerge from pandemic, pledging in a video message this week to intensify the campaign significantly in the coming weeks.

“Everyone must do his part to contain this spread of this virus,” Draghi said Tuesday. “But above all, the government must to its part. Rather, it must try to do more every day. The pandemic is not yet defeated.”

The vaccine is the only way out, Zanolini concurs. He sees all around him that people have grown weary of the restrictions, and are getting relaxed—too relaxed—with gatherings, distancing and masks.

Source: Read Full Article